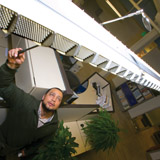

PHOTOS: Jim Block

Next-Gen Environmentalist

David Brower

2009 Conservation and Resource Studies

“Yes, we are missing David Brower,” says David Brower. “We could use a voice like that, a charismatic leader — someone people can rally behind. I think his unwillingness to compromise was infectious for people.” He’s referring, of course, to his late grandfather, David Ross Brower, the feisty, much-loved activist whom writer John McPhee famously dubbed the “archdruid” of the environmental movement.

This Brower, however — David Cornelius, son of writer Kenneth — isn’t looking to follow in his grandfather’s footsteps; he shares similar values and goals, but the path he has chosen is different. He belongs to the next generation of environmentalists, who, rather than storming battlements, seek to weave the tenets of environmental stewardship into the fabric of everyday life.

“People say, ‘Oh, you’ve got big shoes to fill,’ but I don’t feel that way,” he says. His grandfather’s and father’s legacy to him, he believes, is the ability and confidence to find his own path. “My grandfather wouldn’t want me to be exactly like him.”

Currently Brower is immersed in the technologies of energy efficiency. As a project manager for consulting firm ICF International, he works on the San Francisco Energy Watch program, which provides rebates to businesses and homeowners who invest in energy-saving measures.

Since 2007, Energy Watch, a joint project of PG&E and the city’s Department of the Environment, has paid out more than $17.5 million in incentives. Some 5,500 commercial and multifamily properties — ranging from Glide Memorial Church to the Hotel Nikko — have enrolled, saving an average of $4,600 on their annual utility bills and reducing the city’s carbon emissions by over 52,000 tons.

“I’ve learned a lot about the technical side of things,” he laughs. “I came into the job not knowing anything about lighting or HVAC systems or refrigeration equipment, and now I know a lot — not just about the old equipment that’s out there, but also the new and emerging technologies, like LED lighting.”

This is Brower’s first job since graduating from college. At Berkeley, he wasn’t sure what he wanted to do, but an internship in PG&E’s renewable energy division pushed him in the direction of energy efficiency, as did a class in international rural development policy taught by Environmental Science, Policy, and Management Professor Claudia Carr, where he learned about the exploitation of developing countries’ natural resources. “Many of the environmental and social problems in the world are due to the fight to exploit energy resources like palm oil, peanut oil, crude oil, and so on,” he says. “I wanted to learn more about global energy needs and consumption.”

But the single most important thing he learned at Berkeley was “to think critically — to use your judgment and common sense, because especially today there’s a lot of greenwashing and misinformation. At Berkeley you’re taught to dive deeper into issues ... to question everything you learn.”

While he’s proud of what Energy Watch has achieved, Brower is eager to branch out into other areas of energy efficiency. He’s particularly jazzed about a new pilot program he’s working on for the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC), which uses on-board diagnostic devices to analyze the driving patterns and behaviors of a group of volunteers, with the goal of reducing the emissions caused by inefficient driving.

“At Berkeley you’re taught to dive deeper into issues ... to question everything you learn.”

“We’re going to install miles-per-gallon devices that will serve as a visual representation of how they’re driving,” he says — sort of like smart meters for cars, to allow drivers to see how their behavior affects their car’s performance. “The cool thing is that I have one on my car right now, and ... having that visual aid is kind of like a contest: how well can I drive?” If the pilot program is successful, the MTC may decide to provide rebates to drivers who want to install the devices.

Eventually Brower may head back to graduate school; he’s not sure yet what his focus will be, but he knows his career will always involve tackling environmental issues. “When you’re starting your first job, you’re a little naive — you expect to save the world immediately, and you realize that it takes time and experience to really understand what’s going on, where your niche is, how to fit in and really feel like you’re contributing to better the environment. I’m still trying to do that — I’m way too young to know if I’m headed in the right direction.”

But, “I can’t really see myself doing anything else,” he says. “I don’t think I’d be a good sales guy or a good therapist. The Browers are just kind of built this way.”