By Ann Brody Guy

There are plenty of freshman science classes on campus, but it's safe to say that Introduction to Environmental Studies (ESPM C12, English C77) is the only one in which students are introduced to the scientific method through studying a surrealist painting.

The class, which hints at its unique content by satisfying both science and philosophy breadth requirements, might more aptly be named Introduction to Environmental Thought. It is co-taught by Garrison Sposito, a professor in the department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management (ESPM), whose contributions to environmental science have been honored by the American Geophysical Union and the American Chemical Society, and English professor Robert Hass, former U.S. poet laureate (1995-97) and a Pulitzer Prize winner.

The class is not interdisciplinary in the sense that it brings together the humanistic, literary, and scientific aspects of the environment. Rather, say Hass and Sposito, their point is to show students that those elements are never separate.

They point to their own interests as models: Sposito is a scientist, but also has an abiding interest in the history of modern art. Hass is an accomplished amateur naturalist who sometimes leads field trips to look at Bay Area wildlife.

"Science and the imagination are always in dialogue, always have been," says Hass, who launched the class in 1997.

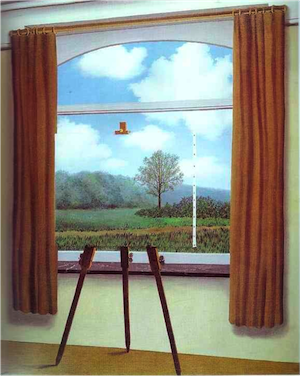

The pair don't waste any time displaying this connection for their students. At the first lesson, Sposito shows the Rene Magritte painting "The Human Condition," which features an easel holding a painting, positioned in front of a window, partially obscuring the view outward. The painting on the easel echoes the landscape outside. Or so we think.

Magritte's painting, Sposito explains to his students, forces a set of assumptions, for example, that what is on the easel is, in fact, depicting what's outside the window, and also forces a particular perspective, aligned so that the painting "looks right" on the easel.

"If you were to move your perspective anywhere other than where Magritte has forced it, the painting on the easel would not seem to depict what is outside the window. It can only work from one perspective," Sposito says. "All these ideas are built into the scientific method."

Following this exercise, students immediately read two essays, each viewing nature through a very particular lens. In his essay "A Windstorm in the Forest," John Muir straps himself high atop a pine tree to "conduct the symphony of a majestic Sierra storm." Joan Didion's "The Santa Ana" is an account of how the notorious Southern California winds cause a spike in the homicide rate, revealing, Hass says, "something profoundly mechanistic about human beings."

"So right away we try to convey to them that they probably have seven or eight attitudes toward nature and the natural world," Hass says. "Some are based on science, like the earth's rotation around the sun. Others may be in their cultural consciousness, like not 'messing with Mother Nature.'"

Laying this groundwork allows Hass and Sposito to have students articulate their understanding of key scientific ideas like evolutionary theory and ecosystem theory, and to think about what people mean when they say "nature."

Deconstructing Content and Language

The premise behind their approach, and the class itself, Hass says, is that as citizens, students will be confronted with choices and will need tools to make sense of them.

"You need to be able to assess claims of fact and claims of value," he says. "The claims of fact are going to come from the procedures of the sciences, and the claims of value are going to come from discourse about nature and human responsibility, and the whole history of the human imagination in relation to the natural world.

Robert Hass (Photo: Peg Skorpinski)

The two say their aim is give students those assessment tools: literary analysis of the text and scientific analysis of environmental processes. For example, the class, which is based in the College of Natural Resources, might look at claims made in an article about drilling for oil in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

"One kind of claim might be that it will destroy the habitat of reindeer. Another might be that they have the science so down that there's almost no chance of any accidents occurring," Hass says. There are indirect claims as well; for example, that drilling will take place in a 'pristine wilderness.' "We look at the word 'pristine' in this context -- what its imaginative meaning is, and whether it has any scientific meaning."

Writing, Field Trips, and Door Prizes

Students lucky enough to get into the class -- there's routinely a long waiting list for the 120 slots -- write biweekly essays, starting with simple applications of their new tools, and gradually take on more subtle, challenging content.

Students keep an environmental journal, go on field trips, and read from a carefully honed syllabus that includes poets such as Walt Whitman, Gary Snyder, Robinson Jeffers, and Wallace Stevens. And Hass and Sposito innovate to keep students engaged:

"We give door prizes, Hass says. I'll ask a question like "What happens to your computer when you throw it out?" A prize goes to the first person who brings back a satisfactory answer.

Hass and Sposito stress that students are not asked to take sides on the issues, and they try not to themselves. "It's going to become evident that we have points of view," Hass says. "Our passion and commitment will show that. But we tell them to question everything, including us."

Keeping Up with Changing Times

Change is central to the character of the class; Sposito and Hass modify it every year based on environmental developments. Last year, people actively involved with the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico presented guest lectures. "We track what's going on right now," Sposito says.

In the 12 years since it began, the class has also changed based on scientific advances. They used to spend a lot of time on the concept of global warming, Hass says, assigning multiple articles on issues such as measuring ice core samples to demonstrate what was happening to the planet.

"The Al Gore movie changed all that," says Sposito, referring to "An Inconvenient Truth," which won Gore an Oscar and a share in the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize. After the movie's release, students started to arrive with some core understanding of issues related to global climate change.

Often, the people who are changing the science are right here at Berkeley. For example, ESPM professor Justin Brashares has given guest lectures on the science of biodiversity conservation for several years.

"Since Justin first came to the class, there have been enormous changes in thinking about biodiversity," says Sposito. It was not clear back then, he says, that a so-called "sixth extinction" of species was actually occurring. "It was like global warming was a few years ago. Now what you see in the scientific literature is that the data are conclusive that there is a sixth global extinction going on, and that we're the cause of it, unlike the other five major extinctions, which were caused by natural phenomena. Justin has been at the forefront of all this work." Brashares is coming back this year to talk about the latest research developments.

"We are fortunate on this campus to have a lot of people who are tremendous resources, and they've been amazingly willing to come and give a lecture to the class about something that's going on right now," Sposito says. Other past guests from the campus community include Energy Secretary Steven Chu, when he was director of Lawrence Berkeley Lab, and food writer Michael Pollan.

Outside visitors are popular as well. Farmer-writer Wendell Berry lectured two years ago, and this year, Steven Kazlowski, a recipient of the Sierra Club's Ansel Adams Award for conservation photography, will present his recent photographs of the Alaskan arctic zone and details of the climate-induced changes there, which he has been documenting for almost 15 years.

"All of these people bring a passion for their work and their own perspectives," Sposito says.

Hass adds, "They also show young people that there are lots of ways to be in the world: journalist, scientist, activist, farmer, artist."

Opening Students' Minds

Do the students get it? The professors receive complaints of "I don't get poetry" or "I have problems with science." But students work closely with their graduate student instructors in lengthy discussion sections, limited to between 10 and 20 students, where they dig deep into their questions.

About halfway through, there's a transformation, Sposito says. "They begin to put it all together and realize that they had been channeled in ways they hadn't been aware of."

"We teach them to appreciate complexity," he continues. "That this world is complex. Ecosystems are complex." This is not a trivial statement, he says. "To appreciate it means to understand that you don't understand."

Hass says that even though they sometimes have disheartening news to deliver about the environment, the overriding themes of the class are hope and resilience. "We are passing the baton on how to be a good environmental citizen."