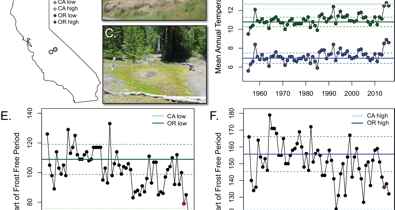

Our new paper on adaptation lag to climate in monkeyflowers is now up online in AmNat! This paper is part of a special issue on Maladaptation, and in the paper we report results from our field work in 2014 at high and low elevation in the Cascades. That summer, former postdoc Nic Kooyers, grew up plants from high and low elevation in Oregon, high and low elevation in California, and segregating offspring in high x low parent crosses within each regional sample.

The 2014 season was during the height of the recent historical drought in the Western US, and the timing of season ending droughts in Oregon was as or more similar to California sites. Consequently, Nic found that low elevation plants from California performed better at low elevation in Oregon than the local Oregon plants. And an high elevation, the high elevation plants from Oregon did the best. An examination of the traits under selection revealed that the seasonal timing of flowering and biomass production were critical at the low and high sites, respectively. Surprisingly, the California plants did the best at their matched elevation even though they were hit the hardest by herbivory.

All of this is consistent with a strong adaptation lag to climate, where populations from areas with historic climates similar to the current climate at a local site will be more fit than the local populations. Although this pattern has been seen in slowly evolving trees or less genetically diverse species, this is the first time this pattern has been seen in a species that should be capable of adapting rapidly due to its large, outcrossing populations that maintain exceptionally high levels of genetic diversity.