Sibele Carvalho-Djotana Puri (left) and Bárbara Nascimento Flores Borum-Kren (right) march as part of the Movimento PluriNacional Wayrakuna, and Indigenous women's movement in Brazil. Photo by Pedro Ivo Carele.

A new study published today in PNAS Nexus revealed for the first time that Indigenous peoples, with officially recognized rights to their territories in Brazil’s embattled Atlantic Forest, reduced deforestation and improved forest cover, outperforming territories that lack formal tenure.

“Our findings contribute to an environmental argument for recognizing the legal land rights of Indigenous peoples in the Atlantic Forest of Brazil, an area that has faced such high development pressures—from urbanization, mining, agriculture, logging and other types of economic development,” said Dr. Rayna Benzeev, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management.

The paper was released as pressure grows on President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, or Lula, to deliver on election promises to roll back policies that have weakened environmental protections and violated the constitutional rights of Indigenous peoples in Brazil. Brazil’s second largest rainforest, the Atlantic Forest, covers around 90,000 km2 and spans 3,000 km of the Atlantic Coast. What remains of the biome is found in rural communities, as well as large urban centers, including Rio de Janeiro, Florianópolis and São Paulo. Deforestation in the Atlantic Forest biome has been prevalent since the early 16th century and rates were highest during the past two centuries, Benzeev said. “In contrast, deforestation in the Amazon started to intensify in the 1970s and more recently escalated again during the Bolsonaro Administration.

Researcher Rayna Benzeev (left) and Guarani Indigenous leader Jerá Poty Mirim. At the southern end of the São Paulo city limits, the Guarani Indigenous community has reclaimed degraded land once used for eucalyptus monoculture. They are reforesting tree species from the Atlantic Forest and are planting traditional foods grown from seeds collected from communities in other states and countries. They have more than 200 varieties of traditional plants, including 9 types of corn, 15 types of sweet potato, four types of peanut, and fruits found in the Atlantic Forest.

A Biodiversity Hotspot

“There has been much international attention and conservation funding directed towards the Amazon, while the Atlantic Forest is in some ways more threatened. It is also a biodiversity hotspot and a top priority ecosystem for reforestation,” said Benzeev, who carried out her research while a doctoral student in the Department of Environmental Studies at the University of Colorado Boulder.

An estimated 80% of the Amazon remains standing, while less than 12% remains of the Atlantic Forest. The region has therefore become a significant focus for reforestation efforts and a source of lessons learned for other reforestation movements around the world.

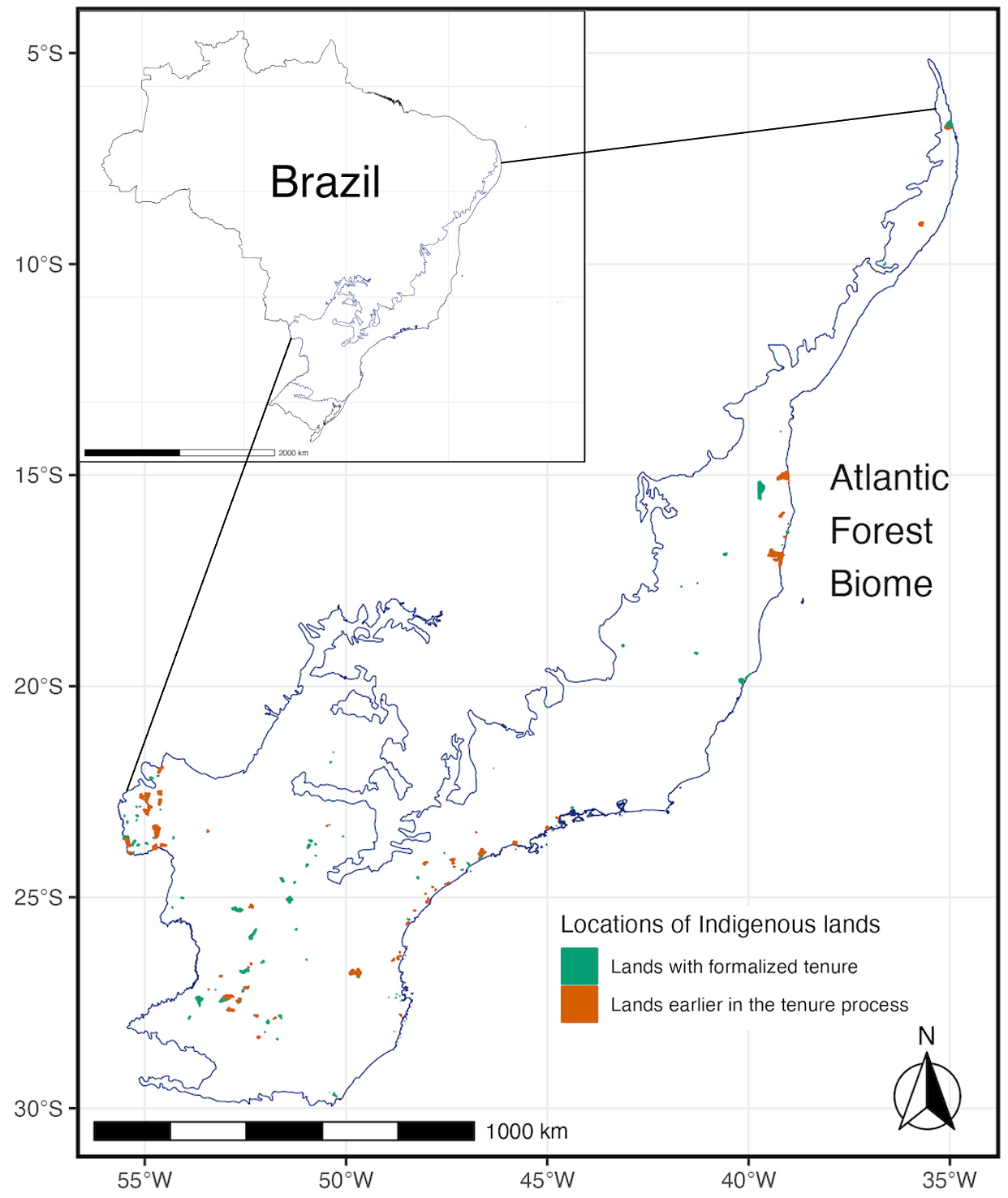

To conduct their research, Benzeev and her co-authors looked at 129 Indigenous territories in the Atlantic Forest and found less deforestation and increased reforestation on lands where Indigenous peoples have formal tenure rights, in marked contrast to Indigenous territories where communities lack rights or are merely in the process of being granted formal tenure.

“Each year after tenure was formalized there was a 0.77% increase in forest cover, compared to untenured lands, on average—which can add up over decades,” Benzeev said, noting the findings could strengthen global efforts to conserve the vulnerable biome that extends across 17 states and has been named a biodiversity hotspot by UNESCO.

"In a biome that has become a model ecosystem for reforestation efforts, it will be important to acknowledge the role of Indigenous peoples in forest protection and reforestation,” Benzeev said. “What support might be needed for Indigenous peoples to continue to maintain forested areas for the long term?"

The importance of land claims

A map of the locations of Indigenous lands in the Atlantic Forest Biome. Map created by Rayna Benzeev.

Currently, demarcation appears to have stalled for many Indigenous communities that had begun the lengthy process of demanding formal land tenure over their ancestral lands, a right granted under the country’s 1988 Constitution.

In fact, since 2012, only one Indigenous territory in the study sample had successfully been granted demarcation.

Of the 726 Indigenous territories submitted to the pipeline for demarcation, 122 remain at the first stage of the process and approved to undergo an investigation by anthropologists; 44 territories are at stage two, which means they have been granted initial approved by FUNAI—the Brazilian National Indian Foundation; 74 are in the third stage of the process — they have been labeled “declared,” but not approved by presidential decree, which is the fourth stage that leads to demarcation. In fact, in the study sample, only one Indigenous territory since 2012 had undergone all the steps necessary for demarcation.

The Brazilian president has moved quickly to reverse his predecessor’s development-first policies, which have included efforts to open Indigenous territories to mining. Brazil has some of the better legal protections on paper for Indigenous rights globally, but failure to enforce its laws, and lack of funding for enforcement agencies, has fueled deforestation.

Dr. Peter Newton, Associate Professor in the Department of Environmental Studies at the University of Colorado Boulder, and co-author on the paper, noted that many indigenous and other traditional communities who live in and around tropical forests depend heavily on those forests, including for subsistence and for income-generation.

“As such, these communities often have a strong incentive to conserve and restore forests,” Newton said. “Institutional support and legal recognition can help them protect forests more effectively.”

Read More:

- When Indigenous communities have legal land rights, this Brazilian forest benefits (CU Boulder Today)

- The best way to save forests? Legally recognize Indigenous lands. (Grist)

Image captions:

Top photo: Sibele Carvalho-Djotana Puri (left) and Bárbara Nascimento Flores Borum-Kren (right) march as part of the Movimento PluriNacional Wayrakuna, and Indigenous women's movement in Brazil. Photo by Pedro Ivo Carele.

Middle photo: Researcher Rayna Benzeev (left) and Guarani Indigenous leader Jerá Poty Mirim. At the southern end of the São Paulo city limits, the Guarani Indigenous community has reclaimed degraded land once used for eucalyptus monoculture. They are reforesting tree species from the Atlantic Forest and are planting traditional foods grown from seeds collected from communities in other states and countries. They have more than 200 varieties of traditional plants, including 9 types of corn, 15 types of sweet potato, four types of peanut, and fruits found in the Atlantic Forest. Photo courtesy of Rayna Benzeev.

Map: A map of the locations of Indigenous lands in the Atlantic Forest Biome. Map created by Rayna Benzeev.