The Tubbs Fire began on October 8, 2017. It became one of the most destructive fires in California’s history, ultimately burning over 36,000 acres in the Sonoma, Napa, and Lake counties. Firefighters battled the blaze, which claimed over 5,000 structures and 22 lives, for weeks until its containment later that month.

ABOUT THE STUDY

The vast size of these fires, as well as their proximity to cities and towns, led to unprecedented loss of life and property, poor air quality through much of the greater Bay Area, and long exposures for those fighting the fires.

Strike teams sent from fire stations in Sonoma and Napa areas, including Santa Rosa, Cotati, Santa Clara and from the San Francisco Bay Area, were quickly deployed to contain these fast moving fires, and because these firefighters needed to be as mobile as possible, they were unable to use their usual personal protective gear, such as an independent air supply, air filters, or turnout gear, leaving them vulnerable to exposures to chemicals that might be released from burning houses, cars, transformers, and garages containing such household items as pesticides, fertilizers and paint.Many worked for hours and days on end without rest or reprieve from the air quality. This presents a unique opportunity to understand fire exposures among firefighters of the region.

A group of 148 firefighters deployed to the Tubbs fires were able to participate in an exposure study a few weeks following their engagement. The study involved collecting and analyzing blood and urine samples from each firefighter, which were then analyzed for levels of toxic chemicals that may have been present on the fire ground. Such chemicals include heavy metals, flame retardants, and substances that are ingredients in some firefighting foam. Each firefighter also completed a questionnaire to indicate their position on the fire fighter crew, duration of deployment, use of fire fighting foam, access to showers and clean turn out gear, etc.

An additional group of 31 firefighters who were not deployed to the Tubbs fires participated in the study as a comparison group

The Tubbs Fire study will help inform future studies aimed at characterizing exposures over the career of a firefighter and relating these exposures to health outcomes.

Click the link below to see the aggregate results from the Tubbs Fire study. Note, in the results section the Tubbs Study is also referred to as the Northern California Firefighter (NCFF) Study.

Tubbs Fire (NCFF) study results

October 30, 2019

The Tubbs Fire Study, also called the Northern California Firefighters (NCFF) Study, was launched to measure some of the chemical exposures experienced by firefighters who responded to the October 2017 Tubbs wildfire, which burned from October 8-31. The NCFF Study included 149 firefighters who were deployed to the 2017 Northern California fires and 31 firefighters who were not deployed to that fire event.

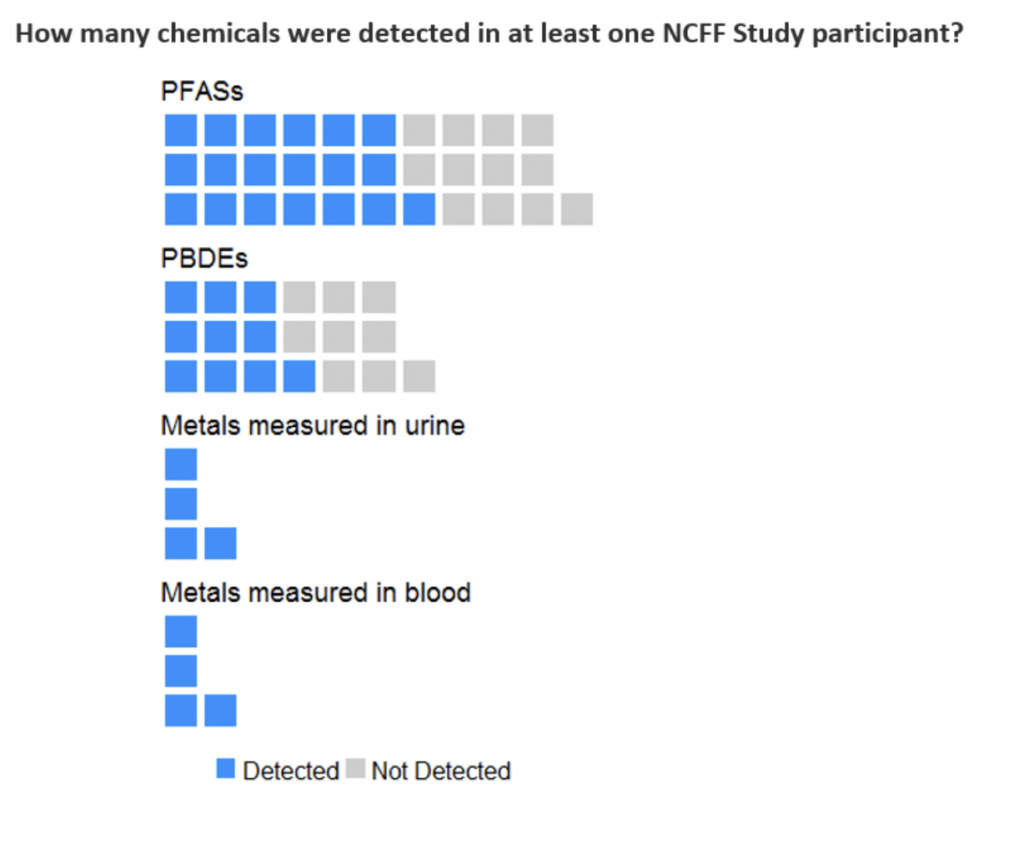

Urine and blood samples collected from participants between November 14-20th were tested for chemicals based on their presence in firefighter gear, equipment, and foams, as well as consumer products commonly used in homes. The study tested firefighters for 55 chemicals, including 5 metals, 31 perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), and 19 polybrominated diphenyl ether (PBDE) flame retardants. Everyone in the study was tested for metals, and 75 people were also tested for PFASs and PBDEs.

We tested for these chemicals because firefighters are exposed to them in multiple ways, including:

- Firefighting gear and foam (PFASs)

- Smoke, ash, burn debris, and soil from wildfire burn areas (metals) and structural fires (metals, PFASs, and PBDEs)

- Consumer products, furniture, and other products from living environments (metals, PFASs, PBDEs)

In future studies, we hope to do sample collection in the field during fire suppression activities or immediately after fire suppression activities are completed, which would allow us to expand the list of chemicals we can analyze.

Metals

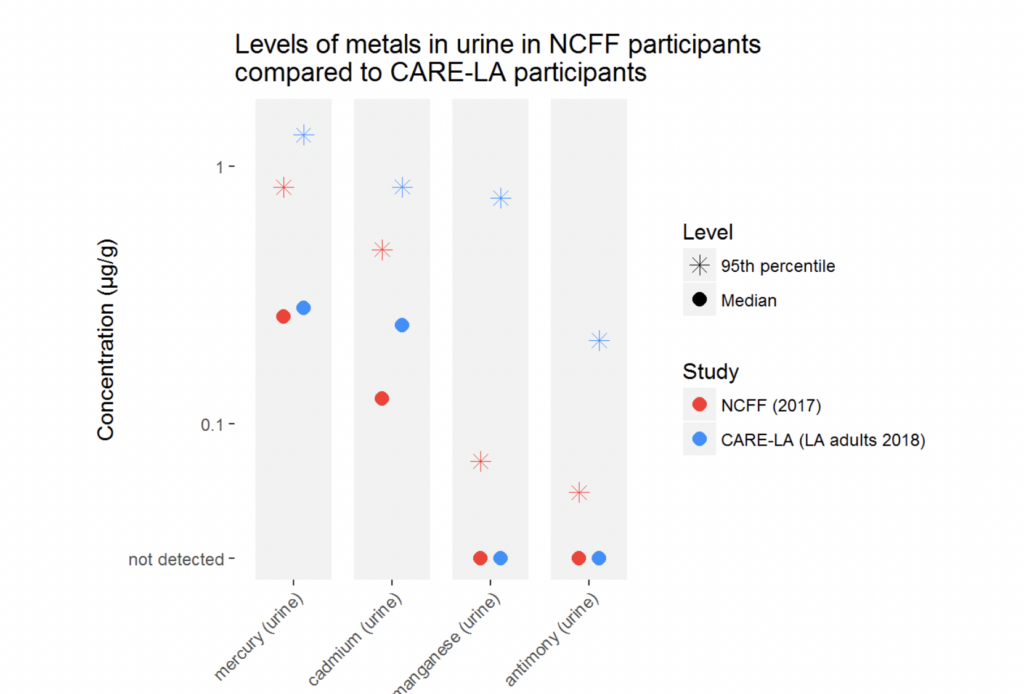

The NCFF (Tubbs) Study tested for five metals (antimony, cadmium, lead, manganese, and mercury). Cadmium, manganese, and mercury were measured in both blood and urine; lead was measured in blood only; and antimony was measured in urine only. Cadmium, lead, manganese, and mercury were detected in nearly everyone’s blood, and cadmium and mercury were detected in nearly everyone’s urine. Antimony and manganese in urine were detected less frequently: 28% had antimony detected, and 11% had manganese detected.

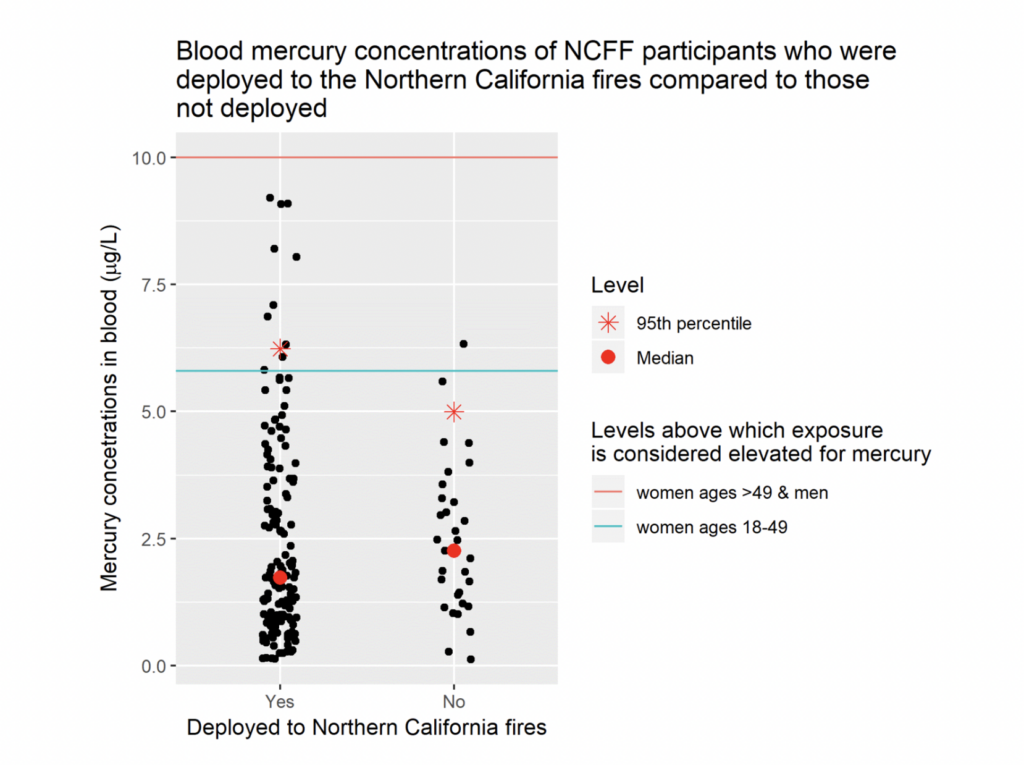

Firefighters who were deployed to that fire event were more likely to have elevated levels of mercury in blood compared to those firefighters who were not deployed. All participants had blood mercury levels below a federal guidance value for men of any age and women over the age of 49 (red line); however, 10 people who were deployed exceeded the guidance value for women aged 18 to 49 (blue line), compared to one person who was not deployed.

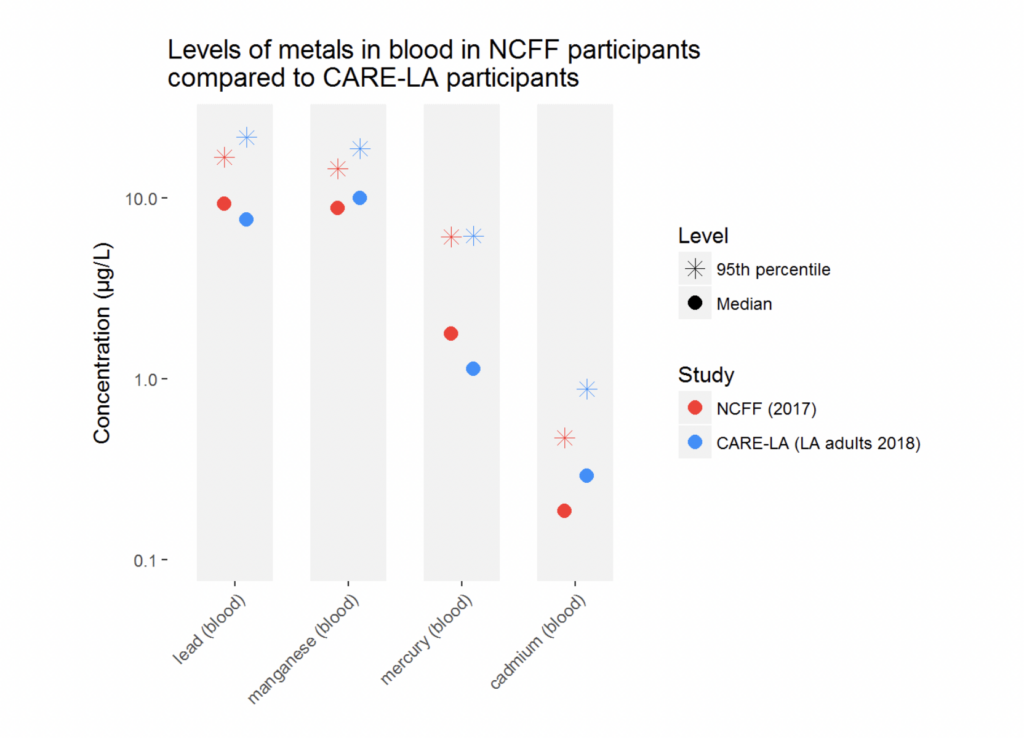

We compared chemical levels from the NCFF Study to levels measured in the California Regional Exposure (CARE) Study. The CARE Study, conducted by Biomonitoring California, is measuring chemical levels in Californians, one area at a time. The CARE Study collected samples from 430 adults living in Los Angeles (LA) County in 2018. Results from CARE-LA are included here to show how NCFF Study results compare to results from an adult non-firefighter population in California. The clearest difference was that NCFF Study participants had lower levels of cadmium in blood and urine compared to CARE-LA participants; otherwise, the levels of metals appeared roughly similar between the two groups (see graphs below).

PFAS

NCFF tested for 31 PFASs. PFASs are used in grease- and water-resistant coatings applied to fabric and food packaging, and in certain firefighting foams and gear.

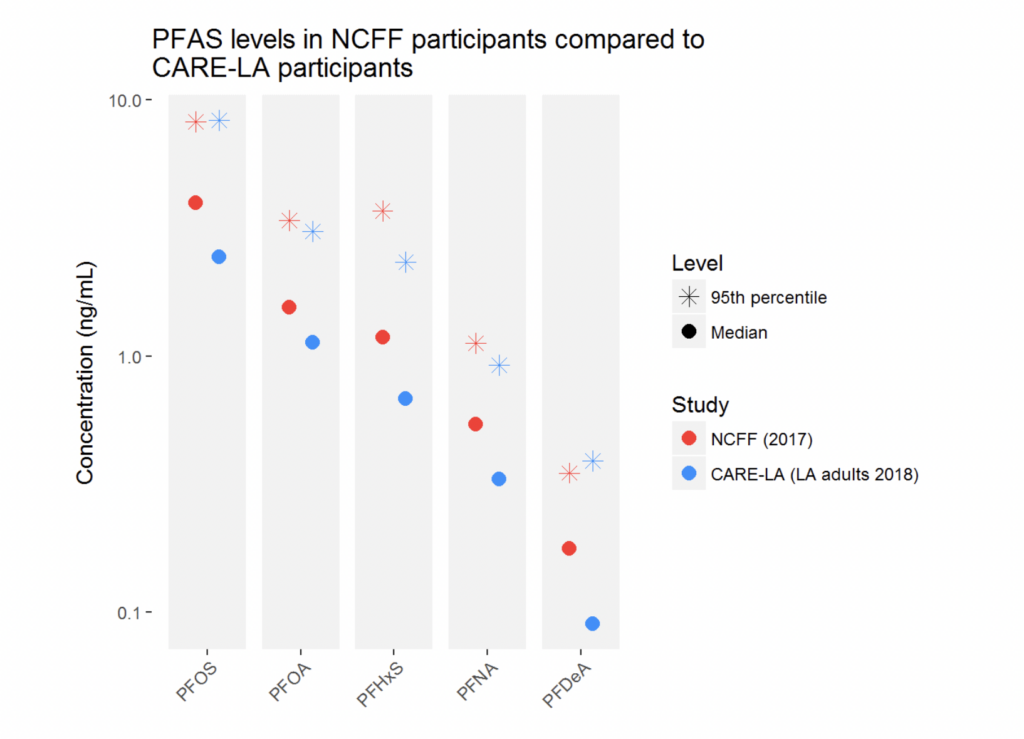

75 NCFF participants were tested for 12 PFASs and 25 of these participants were also tested for an additional 19 PFASs. Five PFASs were detected in all 75 participants who were tested for this group of chemicals. Of the 19 additional PFASs we measured, 12 were not detected in any of the 25 participants. There are several reasons why a PFAS might not be detected, including: it might not be commonly used in consumer products; the body might not easily absorb it; or it might not be easily measured in blood.

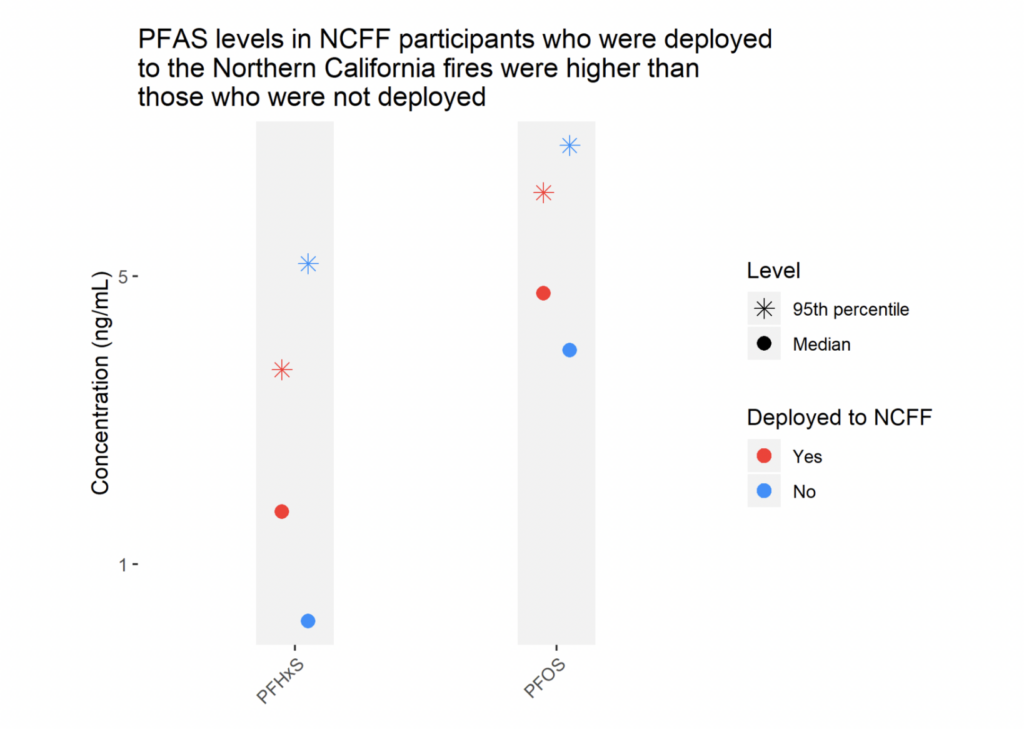

Among NCFF Study participants, PFOS and PFHxS levels tended to be higher among firefighters who were deployed to the 2017 Northern CA fires compared to participants who were not deployed.

NCFF Study participants had somewhat higher levels of most PFASs compared to CARE-LA participants. However, CARE-LA includes a greater proportion of women than the NCFF Study, and women are known to have lower levels of PFASs. This likely contributes to the differences in levels between in the NCFF Study participants and CARE-LA participants.

PBDEs

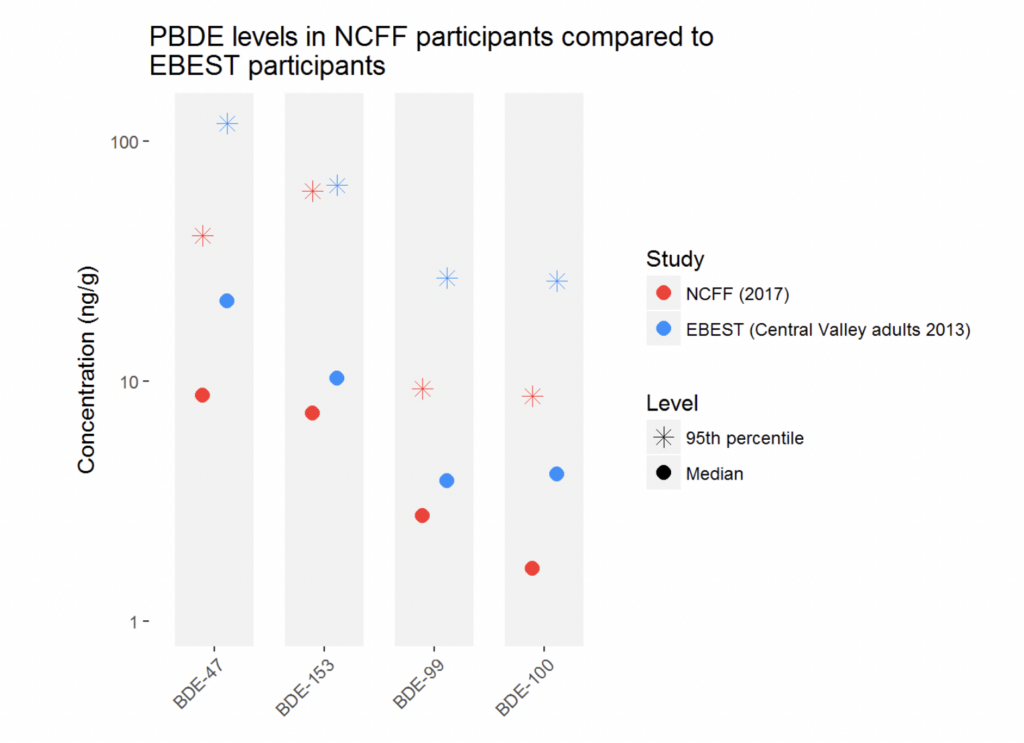

NCFF tested for 19 PBDE flame retardants, which were commonly used in the past in furniture foam, building insulation, plastics, and electronics. Most of these chemicals were phased out of production in the U.S. in 2004. The remaining chemicals were phased out in 2013. However, many people own products produced before the phase-out that contain these chemicals. PBDEs persist in the environment and our bodies for a long time, so they are still commonly found in people’s blood.

75 participants were tested for PBDEs. Three PBDEs were detected in over 90% of NCFF Study participants. Nine PBDEs were not detected in any participants. Most participants had at least four PBDEs detected in their blood sample.

We compared PBDE levels in NCFF to levels measured in the Expanded Biomonitoring Exposures Study (EBEST). EBEST was conducted by Biomonitoring California in 2013 and included 341 adults living in the Central Valley of California. NCFF Study participants, who were tested in 2017, had lower levels of PBDEs compared to EBEST participants. This difference is probably due to decreasing exposures to PBDEs after the phase out of these chemicals. There are no newer population-based studies of PBDEs in California to compare to the NCFF Study population.