- If you want to use the app offline (e.g., in the forest), you need to use the Survey123 app. The Survey123 app allows you to save your observations in the “outbox” when you’re offline, and then submit them when you get back online. There is no cost.

- Location: you can choose to either share the location of the observation or to keep all data private so that only you see it (see privacy note below); alternatively, you can drag the location to a neutral point, e.g. to the KDNR building or off-shore in ocean

- Follow the prompts to fill out information on plant, wildlife, fish, climate/weather, hydrology and/or cultural use quality

- Choose privacy/security/confidentiality settings to determine who can see your observation information: Just you, KDNR staff, other App users, or the public (Note: no location data will ever be shared with the general public).

- To collect information offline, save the point to the “Outbox” and when you’re back in service to into the Output and submit the observations (Important – no one will see your observations until you submit them)

- To provide feedback or suggestions for improvement to the KDNR Citizen Science Tool App manager, please enter comments in the last question at the end of the form

- For troubleshooting support, please contact the KDNR Citizen Science Tool App manager, Christopher Weinstein at: cweinstein@karuk.us

Recovery vs. transformation after the 2020 fires

Many thanks to Earl Crosby and Bill Tripp for contributing to this story

In September and October 2020, the Slater and Devil Fires burned over 150,000 acres and devastated the town of Happy Camp, located within Karuk Ancestral Territory. Earl Crosby, Deputy Director of Karuk Dept. of Natural Resources’ (KDNR) Watersheds Branch, was assigned as a designated Tribal Representative to that fire. He recounts how he and other community members did their best to ensure communities stayed together even as Siskiyou County officials tried to forcibly evacuate residents. During the fire, he witnessed how Pacific Power & Light “ran roughshod” over people and places within and around Happy Camp. Their clearing of right-of-ways to restore power took out any tree, live or dead, hardwood or softwood, that got in the way of power lines. Crosby and Bill Tripp, Director of KDNR, call out how even Black Oaks, an important cultural species, were cut and dumped without consultation. Ever since the fire until now, KDNR has also been interfacing with the US Forest Service as they plan post-fire salvage logging

As he has spoken on and written about many times (see here and listen here), Tripp says the 2020 fires and the official US response and recovery efforts are all “precursored by a century or more of mismanagement.” By taking local Indigenous people out of the system and moving to extraction-based land management, the US has put the Karuk and other Tribes into “a situation where we have to respond to the fact that they’re responding to the mess they’re creating.” Tripp views this situation as a fundamental and major socio-environmental injustice. He calls out that species like the Blacks Oaks will be the real saviors. The name of Happy Camp in Karuk translates to “the place where Hazel creek flows through.” And where does Hazel grow? It grows where Black Oaks grow and where healthy fire is, Tripp noted. Collaboration between Indigenous governments and communities and the US government and settler communities is happening more and more. But the entire situation in and around the horrific Slater Fire set some of those relationships back and “revives that generational pain of cultural genocide.”

Crosby and others are now working to transform the fire emergency response and recovery efforts into forest restoration to promote long-lasting wellbeing of the forests and their communities. They are asking “what does the landscape need to take fire again?” and are carefully marking culturally important trees to leave, prior to salvage logging, so they can re-seed and revegetate on their own. KDNR is working with a local mill in Yreka to purchase the salvaged fir, pine, and incense cedar, which will provide seed money for other restoration efforts. The plan is to have fuels reduction treatments complete by this summer, while restoration efforts will likely ramp up next year.

Also, Crosby hopes to get more and more community members involved, particularly in helping ensure that invasive plants like Scotch Broom and Himalayan Blackberry don’t take over and ruin the chances of native grass seedbank recovery. KDNR also obtained a good number of sugar pine logs and other cultural species (due, unfortunately, to the harmful excesses of the fire response and recovery) and will be working with community members to learn and hone traditional skills for canoes and ceremonial structures. Part of this restoration work also includes advocacy to reintroduce cultural burns to reduce the risk of catastrophic fires like the Slater Fire. To that effect, on March 17th, the Karuk Tribe and a diverse coalition of partners released Good Fire: Current Barriers to the Expansion of Cultural Burning in California and Recommended Solutions, a comprehensive report outlining challenges and policy solutions for better managing wildfires in California.

One year in for the Tishaniik Community Farm and KDNR foodbox projects

Many thanks to Bill Tripp, Jasmine Harvey, and Earl Crosby for contributing to this story

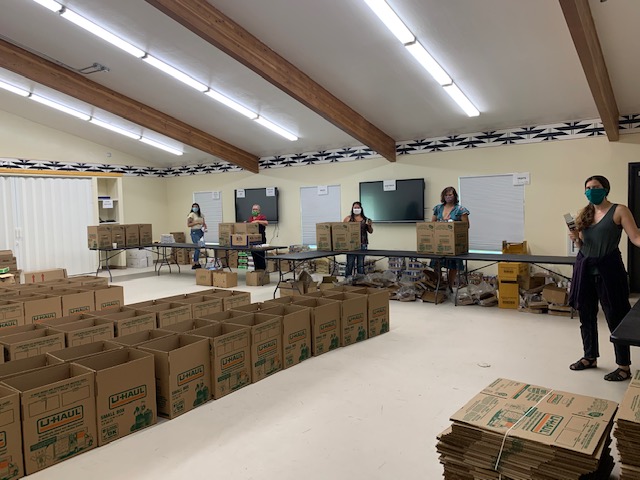

In March 2020, Karuk Dept. of Natural Resources (KDNR) employees and volunteers knew food security would be a top priority as the pandemic crashed across the region. Even as employees were put on administrative leave due to the shutdown, they were adamant about ensuring their communities had food. Fallow organic farmland owned by the Tribe became the Tishaniik Community Farm (the Farm) while, independently, a foodbox distribution program took shape. One year later, these now-intertwined KDNR efforts have grown, shifted, and adjusted, but food security for the community remains central.

This spring, Jasmine Harvey, KDNR Outreach and Sustainability Planning Coordinator, is looking forward to a “bigger head start” for the Farm as they explore self-sustaining activities. Central to the Farm mission is that it is in service to the community, and that the crops grown and harvest distribution remain culturally appropriate. After all, as KDNR Director Bill Tripp reminds, “we’ve avoided becoming farmers for over a hundred years” (despite constant pressure from colonist governments). And, the same time, Karuk members and all those within Karuk Ancestral Territory do eat a lot of farmed produce. KDNR remains centered on revitalizing traditional food and fiber resources in the Territory while simultaneously investing in increased community access to fresh fruits and vegetables through their farm and food box programs. New developments include hiring a Garden Manager and investing in a tractor with implements and preservation equipment (for canning and drying). Additionally, KDNR anticipates leveraging cultural food distribution networks (identified as key to food security under a previous Karuk-UC Berkeley Collaborative project) as they expand Farm and foodbox distribution systems.

Success of the Farm and foodbox distribution program during COVID relied on support from Tribal Council, committed KDNR employees, and a slew of volunteers. While most Tribal offices were shut, multiple KDNR employees were able to come off administrative leave since their food security responsibilities were categorized as essential or part of the COVID emergency response. KDNR also successfully partnered with the Karuk Health Department to develop culturally-appropriate healthy meals for community members in need, building up the capacity of both departments to provide better service. As Earl Crosby, Deputy Director of KDNR Watersheds Branch, puts it, “a lot of people pulled together” to make all of this happen.

Even as these projects become part of abiding programs and systems within DNR, Jasmine Harvey wants to keep the grassroots energy of the past year. Fundamental to the success of the Farm and food box programs have been collective financing and volunteer efforts which means YOUR involvement is needed!

Contact Jasmine about (COVID-safe) volunteer opportunities at jharvey@karuk.us and/or consider donating to DNR’s capital campaign. This campaign feeds into the Endowment for Eco-Cultural Revitalization, a long-term funding mechanism for KDNR and related work within the Karuk Ancestral Territory. Here’s to that head start for spring 2021!

Centering land management and community wellbeing: the SAFE project

This year, the Karuk Tribe (KDNR), Blue Lake Rancheria (Sustainability Office) and Schatz Energy Center (Schatz Center at HSU) have come together around their shared motivation to provide resilient technology that helps people manage smoke, air quality, and energy. The realities, needs, and visions around fire sit squarely in the middle of that. Their 2.5 year project, funded by the California Strategic Growth Council, is entitled “Smoke, Air, Fire, Energy (SAFE) in Rural California: Energy and Air Quality Infrastructure for Climate-smart Communities.” Peter Alstone, Faculty Scientist at the Schatz Center, notes that the project was developed to lift up the particular strengths of each partner. The Karuk Tribe has a long history and practice of using fire on the landscape and understanding how good fire can be beneficial. The Blue Lake Rancheria is a regional leader in deploying advanced microgrids for the community. Researchers through the Schatz Center hold expertise on designing clean energy systems and doing analysis and design for air quality systems.

The past few weeks have brought the needs and visions of this project uncomfortably close to home. As Peter expresses it, “we don’t want to see what’s happening right now [with the wildfires and smoke] continuing.” Instead, the project leads center the benefits of controlled, prescribed fires in Indigenous hands and the associated priority of keeping community members healthy from smoke. Additionally, during those good fires and wildfires alike, communities need resilient, locally-owned energy systems. Right now, just when people need air filtration the most, energy sometimes gets turned off. This research project seeks to make a strong case for these prescribed fires, air quality, and resilient energy being priorities at all levels and types of government. Peter calls the SAFE project a “call to action that’s backed up with indigenous knowledge practice and belief systems and Western science.”

And soon, the SAFE project team will be connecting with local communities! The project kicks off this fall and will be ramping up for community engagement in early summer 2021. They intend to be closely engaged during the next fire season. The project’s goals include developing plans that are actionable for local communities, identifying sources of funding for carrying out those plans, and understanding better how these air, fire, smoke and energy systems intersect in lived reality.

Time to overhaul our systems: a conversation with Bill Tripp

“We need to resolve the fact that our solutions to today’s problems are considered unnatural. Fire exclusion is unnatural. I can’t say I completely understand the politics of individuals and how that is in play in the discussion, nor do I feel I need to, because I know my story and I respect the story of others. It is, after all, the outcomes of our collective action that will ultimately be the measure of our resolve.” – Bill Tripp

Let’s start with the current situation. Two weeks ago, smoke readings at local monitoring stations in the Klamath Basin were well in excess of 700 AQI (for more on AQI). This is “beyond hazardous” according to Bill Tripp, KDNR Director of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy. Our harsh and traumatic reality of ongoing hazardous smoke amidst devastating wildfires comes amidst ongoing, strengthening calls for careful, caring pathways out of our current fire and smoke cycles (see here for a recent example of such a call). Bill notes that the Clean Air Act’s regulations on human-caused smoke actually feeds into the problems we’re living through now and getting in the way of getting ahead.

While the terms ‘fire exclusion’ and ‘climate change’ are being bandied about a lot these past few weeks across California, Bill points to the root cause of “removing Indigenous people from the ecosystem” (see here for more insight on that from Bill and others). This means that certain current pending solutions such as retrofitting homes and other buildings to keep people breathing healthy during worsening fire seasons will only go so far. What is missing…and actively regulated against…are such solutions as burning tanoak stands at night because that is when folks are in their homes. (Such a local solution is banned due to regulators not wanting smoke to settle in the Klamath Valley.) Piecemeal solutions that don’t get to root causes, or come one by one, will remain just that, piecemeal.

To address these gnarly intertwined problems, we must rethink our systems. Our natural resource management systems, our ‘natural’ disaster emergency response systems, our funding systems. Bill cites the KDNR endeavors with high potential with the Western Klamath Restoration Partnership, Píkyav Field Institute, and the Karuk-UCB Collaborative, among others. As a director, his mind goes to: how do we support this work long-term? If Tribal employees and community members keep having to shift their work just to match grant cycles and funder priorities, the solutions will, again, remain piecemeal. Bill points to some current hopeful conversations happening in the UC system about their history and role as land grant institutions (see here for “UC Land Grab” series). Such conversations and the actions stemming from them could bring about big, lasting change, addressing those root causes of removal of Indigenous people and systemic racism. In funding, in enabling further cultural Indigenous fire management, in ensuring community health and wellbeing. (Learn and connect about this through #EndowActionNow)

Black Lives Matter: Message of solidarity in action

Our Karuk Agroecosystem Resilience Initiative: xúus nu’éethti team has been mourning and reflecting on the recent police killings of Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Justin Howell, Sean Monterrosa, and Jamel Floyd, among countless others, and discussing the ongoing pattern of sanctioned violence against Black and non-Black Indigenous people and People of Color (BIPOC) by law enforcement officers. In our personal and professional lives, as well as with each other, we have been discussing approaches to radically reform policing, criminal justice and law enforcement institutions in our communities, as well as strategies for addressing systemic racism and white privilege in research in environmental science, food studies and conservation fields more specifically. We have been grappling with how to best practice anti-racism and centering of Black, Indigenous, and Peoples of Color first in our work, research and advocacy and how to deepen our anti-racist learning, commitments, practices and alliances collectively and individually. The Karuk-UCB partnership works to recognize that we are all coming to this conversation from different experiences, racial backgrounds, and situated perspectives.

Our team is composed of Indigenous and non-Indigenous members, based at different institutions – including the Karuk Tribe Department of Natural Resources, UC Berkeley/UC Agriculture and Natural Resources, and the US Forest Service – and we are involved in different webs of personal and professional relations that are taking time to acknowledge our positionalities so we can act to support the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement and anti-racist practice. Academic partners on the grant affiliated with UC Berkeley’s Dept. of Environmental Science, Policy & Management have also committed to the following actions. Team members with children are drawing on Black Lives Matter Instructional Library as an important resource for youth and teachers.

While taking the present moment to focus on the specific injustices related to police/law enforcement officers killings and violent enforcement actions against Black lives, we have also been discussing connections between patterns of racist policing in Black and Indigenous communities. We align with L. Simpson’s calls for “expressing resistance to all forms of colonial gendered violence” and decolonizing the “systems that create and maintain the forces of Indigenous genocide and anti-blackness.”

It is an anti-blackness intrinsically linked to the genocide, white supremacy, hetero-patriarchy, and colonialism used to maintain the dispossession of indigenous people from our homelands…black and indigenous communities of struggle are deeply connected through our experiences with colonialism, oppression, and white supremacy. Indigenous and black people are disproportionately attacked and targeted by the state, and, in fact, policing in Turtle Island was born of the need to suppress and oppress black and indigenous resistance to colonialism and slavery.

Leanne Simpson, 2014 (Yes! magazine article)

As a team, we pledge to deepen our understanding of structural racism, settler colonialism and white supremacist patterns, and work toward dismantling these systems of oppression. We pledge to have difficult conversations and create a supportive space within our partnership to understand our own privileges and dynamics. We want to support the BLM movement by amplifying the message of justice for the Black community while we mourn the loss of all those that have passed at the hands of sanctioned police violence. Our work is structured around Indigenous voices, but we can step up and center more conversations to affirm that Black lives do matter and support that centering through action.

Specifically, we will be:

- holding dedicated space on weekly calls;

- bringing anti-racism more explicitly into our theoretical frameworks and approaches to doing research and policy advocacy;

- sharing anti-racist reading and training information;

- participating in a 21 day racial equity habit building challenge: https://debbyirving.com/21-day-challenge/;

- amplifying BIPOC scholars and recruiting BIPOC students to participate in our research team;

- focusing on how to more deeply align our food sovereignty and eco-cultural revitalization initiatives with antiracist struggles;

- holding our institutions accountable; and

- uplifting Black and Indigenous-led land and food sovereignty organizations, including: Soul Fire Farm calling for reparations for Black-Indigenous farmers; the National Black Food and Justice Alliance organizing for Black food and land; the Okra Project providing free, delicious, and nutritious meals to Black Trans people experiencing food insecurity; the Black Food Sovereignty Coalition confronting systemic barriers that prevent Black and Brown people from accessing food, place and economic opportunities; and multiple Bay Area Black-led food and land justice organizations, including Common Vision, Urban Tilth, Black Earth Farms, Raised Roots, Acta Non Verba, and Happy Lot Farm & Garden.

Píkyav Field Insitute – K-12 Environmental Education Update

Written by Heather Rickard (K12 Environmental Education Division Coordinator) and Bari Talley (Sípnuuk Division Coordinator)

Píkyav Field Institute staff recognize it’s been a difficult transition for students, teachers and families with school closures and a shift to remote learning, and we sincerely hope this finds you all well. Read on below for an overview of our pre-pandemic K12 lessons with the Karuk Agroecosystem Resilience Initiative: xúus nu’éethti.

Before schools were closed, Happy Camp Elementary 7-8th grade class completed a 4 week series on Fire Ecology and Cultural Fire with DNR’s Fire & Fuels staff.

Orleans Elementary 7-8 th grade class applied fire lessons during a field trip to experiment with DNR’s new Fire Simulation Table with Margo Robbins of KTJUSD and DNR staff including Chook Chook Hillman, Sylvia Van Royen, Scot Steinbring, and Carley Whitecrane.

Laser pointer simulating fires on ridges

Recreating topography with sand

Orleans Elementary 3-6th grade class completed a 5 week series on the social, cultural, and ecological dimensions of Climate Change. Here’s a few pictorial highlights:

Yellow foot mushroom

Resiliency through the lens of a microscope

Climate change through tree rings

Students examine effects of climate change

For access to Nanu’avaha Curriculum and so much more, go to https://sipnuuk.karuk.us/ or contact Bari Talley at btalley@karuk.us. For questions about Environmental Education activities above, feel free to reach out to Heather Rickard at hrickard@karuk.us.

We wish you all a great summer! Take care everyone!

Sowing Seeds of Resiliency and Growing Community

Republished with permission from author Jasmine Harvey, Karuk Dept. of Natural Resources

We are in very uncertain times. This year has been marked with massive changes to society from a global pandemic and widespread social unrest, and nobody knows what tomorrow may bring. Although the Department of Natural Resources has always worked to ensure that our communities aren’t faced with food insecurity, this year our efforts have grown substantially.

Building off of the groundwork of food security projects from many years of dedication, DNR Staff, along with community volunteers and financial support from the Humboldt Area Foundation, have designed and implemented a Community Farm on Tribal Property in Orleans.

Under the Karuk Tribe’s Incident Management team for the COVID-19 response, DNR has taken on planning and implementation of Emergency Support Functions 4 and 11 (Firefighting and Agriculture/Natural Resources, respectively). ESF 11 outlines standard operating procedures to ensure the safe production and distribution of food grown at this community farm. Producing food locally will supply fresh healthy food to the distribution boxes as part of the Tribe’s Covid response, and will also provide safe jobs to local workers who are laid off due to necessary precautions taken to slow the spread.

So far we have planted hundreds upon hundreds of tomatoes, peppers, squash, cucumbers, green beans, and potatoes, and are looking into our options for sustaining what we have and expanding into meat, eggs, mushrooms and fruit production, as well as processing facilities to preserve our harvests.

If you are interested in supporting these efforts or would like to know more about DNR’s food security projects, contact us at (530)-627-3446.

Restoring Access to Native Foods Can Reduce Tribal Food Insecurity

Native Americans suffer from the highest rates of food insecurity, poverty and diet-related disease in the United States. A new study finds that Native American communities could improve their food security with a greater ability to hunt, fish, gather and preserve their own food.

“We know our efforts to revitalize and care for our food system through traditional land management are critical to the physical and cultural survival of the humans who are part of it,” said Leaf Hillman, director of the Karuk Tribe’s Department of Natural Resources. “This study will support our ability to bring that message to the decision-makers who need to hear it.”

The study conducted by researchers at UC Berkeley and four Native American tribes shows that 92% of Native American households in the Klamath Basin suffer from food insecurity.

“How food security is framed, and by whom, shapes the interventions or solutions that are proposed,” said Jennifer Sowerwine, UC Cooperative Extension specialist at UC Berkeley, who led the study in partnership with the Karuk, Yurok, Hoopa, and Klamath Tribes. “Our research suggests that current measures of and solutions to food insecurity in the United States need to be more culturally relevant to effectively assess and address chronic food insecurity in Native American communities.”

Native American tribes in the Klamath Basin seasonally harvest, consume and store diverse aquatic and terrestrial native foods including salmon, acorns and deer. In survey responses, 86% of the participants said they consumed native foods at least once in the previous year. Yet significant barriers, including restrictive laws and wildlife habitat degradation, limit availability and quality of these foods.

While 64% of Native American households in the Klamath Basin rely on food assistance (compared to the national average of 12%), 84% of the Native Americans using food assistance worried about running out of food or had run out of food. This suggests the need to consider more effective solutions rooted in eco-cultural restoration and food sovereignty to address food insecurity in Native American communities.

Study participants strongly expressed the desire for strengthened tribal governance of Native lands and stewardship of cultural resources to increase access to native foods, as well as strengthening skills for self-reliance including support for home food production. Community members suggested solutions including tribe-led workshops on native foods gathering, preparation, and preservation; removing legal barriers to hunt, fish and gather; restoring traditional rights to hunt, fish and gather on tribal ancestral lands; providing culturally relevant education and employment opportunities to tribal members; and increased funding for native foods programs.

While growing evidence suggests that native foods are the most nutritious and culturally appropriate foods for Native American people – and over 99% of people surveyed in the region said they want more of these foods – nearly 70% said they never or rarely get access to the native foods they want.

With the study results indicating that increased access to native foods and support for cultural institutions such as traditional knowledge and food sharing are key to solving food insecurity in Native American communities, Sowerwine and the research team propose including access to native foods as a measure for evaluating food security for Native people.

The assessment is based on 711 surveys completed by households from the Karuk, Yurok, Hoopa and Klamath Tribes, 115 interviews with cultural practitioners and food system stakeholders, and 20 focus groups with tribal members or descendants.

In addition to Sowerwine and Hillman, the study was conducted by post-doctoral researchers Megan Mucioki and Dan Sarna-Wojcicki, and research partners from the Yurok, Karuk and Klamath Tribes.

“Partnering with tribal community members in the research makes the research stronger, and that is especially true in this unique food security assessment,” said Sowerwine. “With the study design grounded in nearly a decade of relationship-building and respectful engagement with our tribal partners, we are confident that our results reflect their priority questions and concerns while contributing valuable new information to the field of indigenous food systems.”

“Reframing food security by and for Native American communities: a case study among tribes in the Klamath River basin of Oregon and California” is published in the journal Food Security. This research was part of a $4 million, five-year Tribal Food Security Project funded by USDA-National Institute of Food and Agriculture-Agriculture and Food Research Initiative Food Security Grant #2012-68004-20018. For full results and recommendations from the project team, see Publications.

Increasing Tribal Ecosystem Resilience in a Changing Climate

Assessing traditional foods after prescribed burning. Klamath Salmon Media Collective photo.

As California and the nation grapple with the implications of persistent drought, devastating wildfires and other harbingers of climate change, researchers at UC Berkeley’s College of Natural Resources are building on a decade-long partnership with the Karuk Tribe and the US Forest Service Pacific Southwest Research Station to learn more about stewarding native food plants in fluctuating environmental conditions. UC Berkeley and the Karuk Tribe have been awarded a $1.2 million USDA grant for field research, new digital data analysis tools, and community skill-building aimed to increase resilience of the abundant cultural food and other plant resources – and the Tribal people whose food security and health depend on them.

Jennifer Sowerwine, UC Cooperative Extension specialist at UC Berkeley and co-founder of the Karuk-UC Berkeley Collaborative, and Lisa Hillman, program manager of the Karuk Tribe’s Píkyav Field Institute. will co-lead the xúus nu’éethti – we are caring for it research project.

“We are delighted to continue our connection with UC Berkeley through this new project,” said Lisa Hillman. “Through our past collaboration on Tribal food security, we strengthened a network of Tribal folks knowledgeable in identifying, monitoring, harvesting, managing for and preparing the traditional foods that sustain us physically and culturally. With this new project, we aim to integrate variables such as climate change, plant pathogens and invasive species into our research and management equations, learning new skills and knowledge along the way and sharing those STEM skills with the next generation.”

UC Berkeley’s College of Natural Resources, UC Agriculture and Natural Resources, and the Karuk Department of Natural Resources will support the project with postdoctoral researchers, botany, mapping and GIS specialists, and Tribal cultural practitioners and resource technicians. Dr. Frank Lake, Research Ecologist and Tribal Climate Change liaison at the US Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station, will contribute to research and local outreach activities. The San Rafael-based Center for Digital Archaeology will help develop a new data modeling system. “This project underscores the enormous successes we have had with these long-standing collaborative partners,” said Hillman.

Project activities include expanding the Tribe’s herbarium (a research archive of preserved cultural plants launched in 2016 with UC Berkeley support), developing digital tools to collect and store agroecological field data, and helping Tribal community members and youth learn how to analyze the results.

The research team will assess the condition of cultural agroecosystems including foods and fibers to understand how land use, land management, and climate variables have affected ecosystem resilience. Through planning designed to maximize community input, they will develop new tools to inform land management choices at the federal, state, tribal and community levels.

All project activities will take place in the Karuk Tribe’s Aboriginal Territory located in the mid Klamath River Basin, but results from the project will be useful to other Tribes and entities working toward sustainable management of cultural natural resources in an era of increasing climate variability. Findings will be shared nationwide through cooperative extension outreach services and publications.

The new project’s name, xúus nu’éethti – we are caring for it, reflects the Karuk Tribe’s continuing commitment to restore and enhance the co-inhabitants of its aboriginal territory whom they know to be their relations – plants, animals, fish, water, rocks and land. At the core of Karuk identity is the principle of reciprocity: one must first care for these relations in order to receive their gifts for future generations.

This work will be supported by the Agriculture and Food Research Initiative Resilient Agroecosystems in a Changing Climate Challenge Area, grant no. 2018-68002-27916 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.