In the rainforests of Borneo, people and wild pigs are fundamentally linked

These deep ties underscore the importance of understanding our broader link to nature.

[image caption]

Ecological and social landscapes are fundamentally linked. From hunting traditions and the geography of port cities to aesthetic values linked to nature, evidence of how biophysical landscapes shape human landscapes—and vice versa—fills our societies.

Recent research led by David Kurz, PhD ’21 Environmental Science, Policy, and Management, explores one of Borneo’s most enduring human-environment links: Indigenous hunting of bearded pigs. Published in npj biodiversity, the study shows how these hunting traditions—alongside environmental factors—influence the distribution of bearded pigs in Borneo.

“It is exciting to be able to show quantitatively what we know intuitively to be true—that humans and nature are fundamentally linked,” explained Kurz, now a postdoctoral fellow in environmental science at Trinity College.

Building a Model

[image caption]

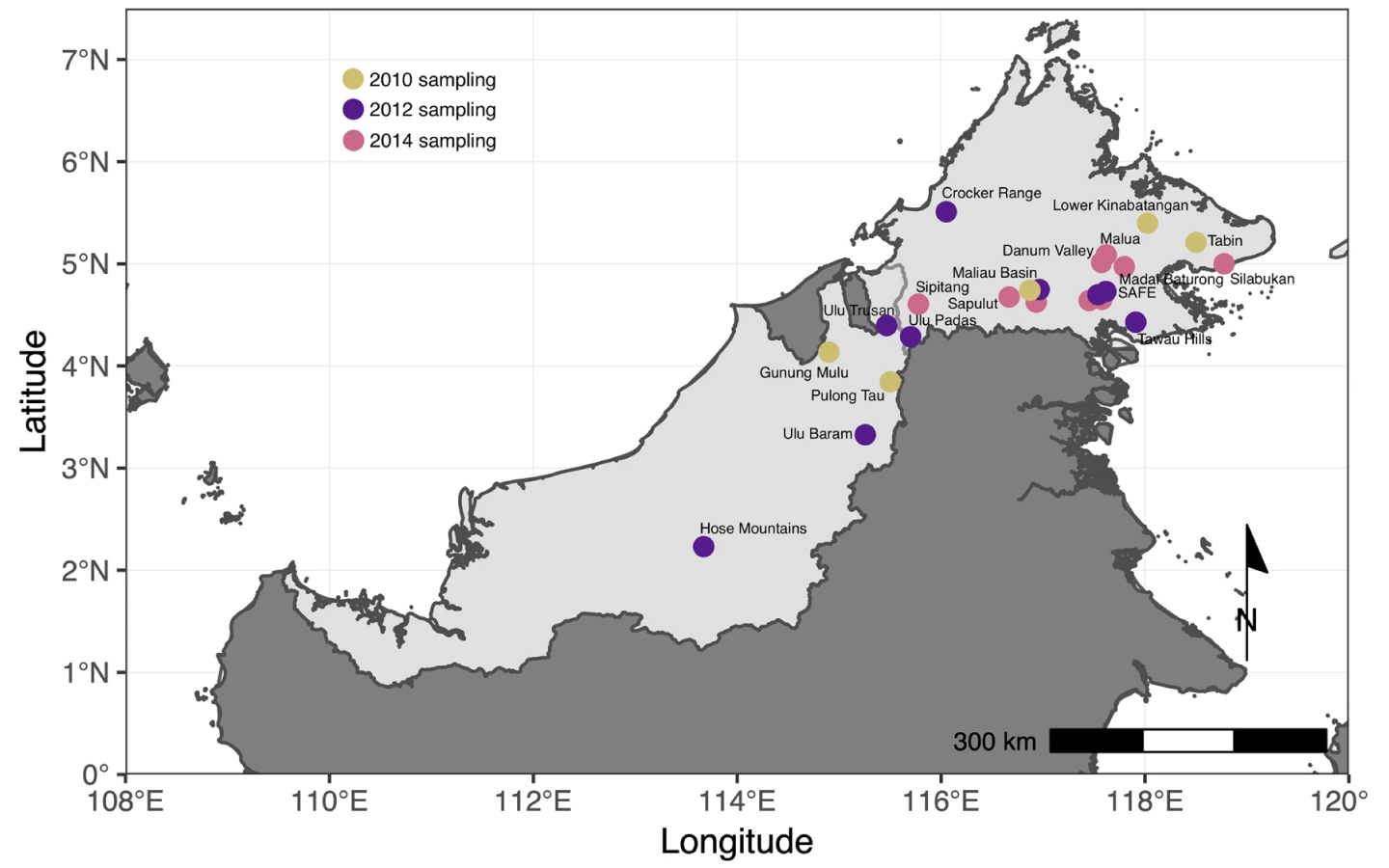

The project builds on research Kurz began as a graduate student in the labs of Professors Justin Brashares and Matthew Potts. To better understand the species’ spatial distribution, the authors—who also include researchers from Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, and other institutions—used quantitative models to assess the influences of social and environmental factors on the locations of the bearded pigs.

Researchers paired observations from remote-triggered cameras scattered throughout rainforests in East Malaysia with figures from the Malaysian census and environmental data from Google Earth Engine. The authors also used an existing metric of hunting accessibility to include the influence of landscape resistance and population density in the model.

According to the findings, bearded pig occurrence on the cameras was found to be associated with certain environmental factors. For example, pig occurrence was positively associated with proximity to water; the authors hypothesize that water could help the pigs cool down in the warm tropical environment, or that fig trees near water may provide a source of food.

The results also showed a relationship between Indigenous hunting communities and hunting accessibility. The researchers estimated that pig occurrence in remote locations was positively associated with a higher proportion of Indigenous pig hunting communities, whereas they estimated that pig occurrence in areas closer to roads and settlements was associated with a medium to low proportion of the same communities.

Supporting Indigenous Practices

The study provides quantitative evidence for the sustainability of Indigenous pig hunting traditions and pig occurrence across different landscapes. In so doing, the research lends empirical support for Indigenous hunting rights, which have been held by local communities in Malaysian Borneo for thousands of years. Bearded pigs are important to Borneo’s Kadazandusun-Murut (KDM) communities in Sabah, and Iban communities in Sarawak. Not only are the pigs a preferred source of meat, but hunting is an important cultural touchstone for many.

[image caption]

During their research, a strain of African Swine Fever (ASF)—which causes high mortality in domestic and wild pigs—broke out within their study area. The outbreak generated concern among some local communities according to co-author Esther Lonnie Baking, a KDM PhD student at Universiti Malaysia Sabah.

“The low supply of pig meat has affected both seller and consumer, where the price per kilogram has increased three times higher than the normal price prior to ASF,” she said. “People rather gave up buying pig meat.”

According to Kurz, bearded pigs are capable of reproducing quickly—with enough food, a sow can give birth to a dozen or more piglets in a single year. The authors suggest that Indigenous leaders and government officials can better assess the sustainability of hunting practices during ASF outbreaks by comparing the recovery trajectory with baseline population estimates.

The deep ties between people and pigs in Borneo underscore the importance of understanding our broader link to nature. Including human influences—like wealth, noise, hiking and recreation, light pollution, fishing practices, and the distribution of urban parks—in wildlife studies can help researchers determine the ways people shape wildlife distributions.

Understanding the fuller picture of human-environment links, Kurz said, can help us balance long-term social and ecological sustainability.

Additional UC Berkeley co-authors include professors Justin Brashares and Matthew Potts, and postdoctoral researcher Thomas Connor.

Read More