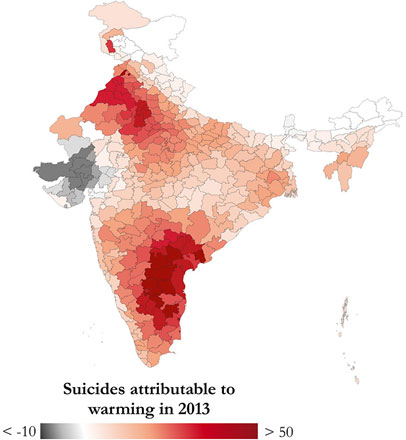

Climate change has already caused more than 59,000 suicides in India over the last 30 years, according to estimates in a study published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) that suggests failing harvests that push farmers into poverty are likely the key culprits.

Tamma Carleton, a PhD. candidate in the department of Agricultural & Resource Economics, discovered that warming a single day by 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) during India’s agricultural growing season leads to roughly 65 suicides across the country, whenever that day’s temperature is above 20 degrees Celsius (68 degrees Fahrenheit). Warming a day by 5 degrees Celsius has five times that effect.

Carleton projects that today’s suicide rate will only rise as temperatures continue to warm.

While high temperatures and low rainfall during the growing season substantially impact annual suicide rates, similar events have no effect on suicide rates during the off-season, when few crops are grown, implicating agriculture as the critical link.

This study helps explain India’s evolving suicide epidemic, where suicide rates have nearly doubled since 1980 and claim more than 130,000 lives each year. Carleton’s results indicate that 7 percent of this upward trend can be attributed to warming that has been linked to human activity.

Soaring temperatures, despair

More than 75 percent of the world’s suicides are believed to occur in developing countries, with one-fifth of those in India alone. But there has been little hard evidence to help explain why poor populations are so at risk.

“It was both shocking and heartbreaking to see that thousands of people face such bleak conditions that they are driven to harm themselves,” Carleton says. “But learning that the desperation is economic means that we can do something about this. The right policies could save thousands.”

The study demonstrates that warming — forecast to reach 3 degrees Celsius by 2050 — is already taking a toll on Indian society. Using methods that she developed in a previous paper published in the journal Science, Carleton projects that today’s suicide rate will only rise as temperatures continue to warm.

Optimists often suggest that society will adapt to warming. But Carleton searched for evidence that communities acclimatize to high temperatures, or become more resilient as they get richer, and found none in the data.

“Without interventions that help families adapt to a warmer climate, it’s likely we will see a rising number of lives lost to suicide as climate change worsens in India,” Carleton says.

Carleton says she hopes her work will help people better understand the human cost of climate change, as well as inform suicide prevention policy in India and other developing countries.

“The tragedy is unfolding today. This is not a problem for future generations. This is our problem, right now,” she says.

Which policies will help prevent suicide?

Debate about solutions to the country’s high and rising suicide rate is contentious and has centered around lowering economic risks for farmers. In response, the Indian government established a $1.3 billion crop insurance plan aimed at reducing the suicide rate but it is unknown if that will be sufficient or effective.

“Public dialogue has focused on a narrative in which crop failures increase farmer debt, and cause some farmers to commit suicide. Until now, there was no data to support this claim,” says Carleton.

More than half of India’s working population is employed in rain-dependent agriculture, long known to be sensitive to climate fluctuations such as unpredictable monsoon rains, scorching heat waves, and drought. A third of India’s workers already earn below the international poverty line.

This study’s findings indicate that protecting these workers from major economic shortfalls during these events, through policies like crop insurance or improvements in rural credit markets, may help to rein in a rising suicide rate.

Impacts beyond agriculture

Heat drives crop loss, Carleton contends, which can cause ripple effects throughout the Indian economy as poor harvests drive up food prices, shrink agricultural jobs and draw on household savings. During these times, it appears that a staggering number of people, often male heads of household, turn to suicide.

The Indian government established a $1.3 billion crop insurance plan aimed at reducing the suicide rate, but it is unknown if that will be sufficient or effective.

Carleton tested the links between climate change, crop yields and suicide by pairing the numbers for India’s reported suicides in each of its 32 states between 1967 and 2013, using a dataset prepared by the Indian National Crime Records Bureau, along with statistics on India’s crop yields, and high-resolution climate data.

To isolate the types of climate shocks that damage crops, Carleton focused on temperature and rainfall during June through September, a critical period for crop productivity that is based on the average arrival and departure dates of India’s summer monsoon.

She cautions that her estimates of temperature-linked suicides are probably too low, because deaths in general are underreported in India and because until 2014, national law held that attempted suicide was a criminal offense, further discouraging reporting.

Carleton was a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University and is a recipient of the Science to Achieve Results Fellowship awarded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.