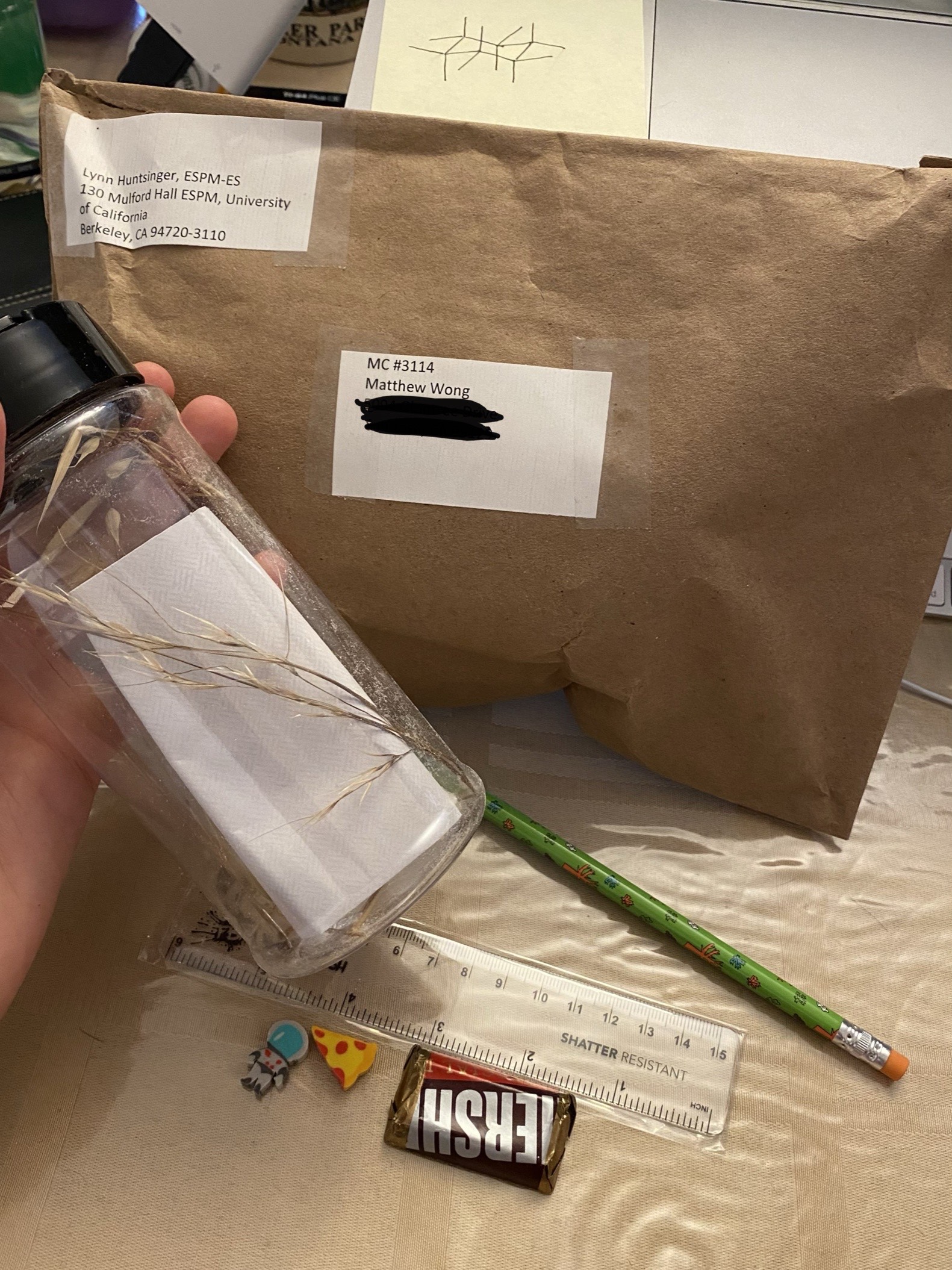

Student Matthew Wong shows some of the components mailed out by professor Lynn Huntsinger for her course on woodland and grassland ecology. From home, students could practice methodology for environmental assessments without ever entering a lab. Photo by Matthew Wong.

One day in October when Matthew Wong checked his mailbox, he found a large envelope with a UC Berkeley return address. Inside the lumpy package was a plastic jar, a packet of borax, a ruler, grass seeds, and a few pieces of grass.

This was no random assemblage of junk. Rather, it was a social distancing-compliant take-home experiment that environmental science, policy, and management professor Lynn Huntsinger had designed for the students in her Woodland and Grassland Ecology course. With these materials and instructions, students would learn to evaluate soil texture while sheltering in place, practicing key methodology for environmental assessments without ever entering a lab.

“It was definitely refreshing from the other classes, which mostly just involved watching videos online and completing worksheets,” says Wong, a second year student majoring in chemistry. “I found this sort of lab experience a welcome and energizing change of pace.”

If unconventional, such mailed experiments are one way in which Rausser College professors are adapting, using novel strategies to keep lessons engaging and hands-on as students study from home during the COVID-19 pandemic.

After collecting soil samples near their homes, Huntsinger’s students placed the samples into the jar with water and borax then shook it vigorously. Once the contents settled, the stratification of the soil could be measured to determine whether the ground is sandy loam, clay loam, or another soil type—designations that natural resource agencies use to classify and evaluate field sites. In another component of the experiment, native and non-native grasses were grown in the Oxford greenhouses and students conducted a comparative analysis on how native and non-native grasses fare, measuring root and top-growth biomass and other indicators. The goal was to further understand the displacement of California’s native grasses by species from other Mediterranean regions.

By following instructions, students are able to evaluate soil for grassland ecology fieldwork at home. Mailed experiments such as this one are a creative method that faculty have adopted during remote instruction this semester. Photo by Matthew Wong.

For the students who spend many hours with Zoom lectures or other virtual platforms, such methods provide a welcome break from routine and screen time. “It was really fun,” Wong says of the experiment. “I actually attended Professor Huntsinger’s office hours and asked if we could do another interactive lab.”

Beyond the lesson itself, Huntsinger had another goal in mind when mailing out the kits. “The students could have gotten all of the things at a store or at home,” she says. “But sending the kits offered a connection, and it was a chance to welcome transfer students. It was to cheer us all up.” In the packet, she included some chocolate, a pencil, and some colorful erasers for good measure.

Huntsinger has proven to have a knack for innovative teaching in other aspects of remote learning. For her lessons, she even took up time-lapse photography.

Before the pandemic, Huntsinger would bring her lab class in the Oxford Greenhouse, where she could use real plants to demonstrate the comparative growth of native and non-native grasses and explain how nonnative grass has taken over so many landscapes. This semester, she bought a small waterproof camera—designed to monitor progress at building sites—and set it up to record the growth of grasses. With her graduate student Paige Stanley, she also made a video (below) on drying and weighing grass samples. “I tried to do the labs a bit like a cooking show,” Huntsinger says. Because she participated in an outdoor pilot program this fall, students were able to conduct the final steps of the project in person this year, in the lath houses next to the greenhouses, following COVID health guidelines.

CAPTION: This time lapse video was created by professor Lynn Huntsinger for students in her Woodland and Grassland Ecology course. Since students couldn't gather in person due to social distancing, the video helped students understand grass growth, how to measure samples, and the success of non-native grasses in California. She also mailed experiments to her students at home, where they learned to analyze soil samples.

Mycology at home

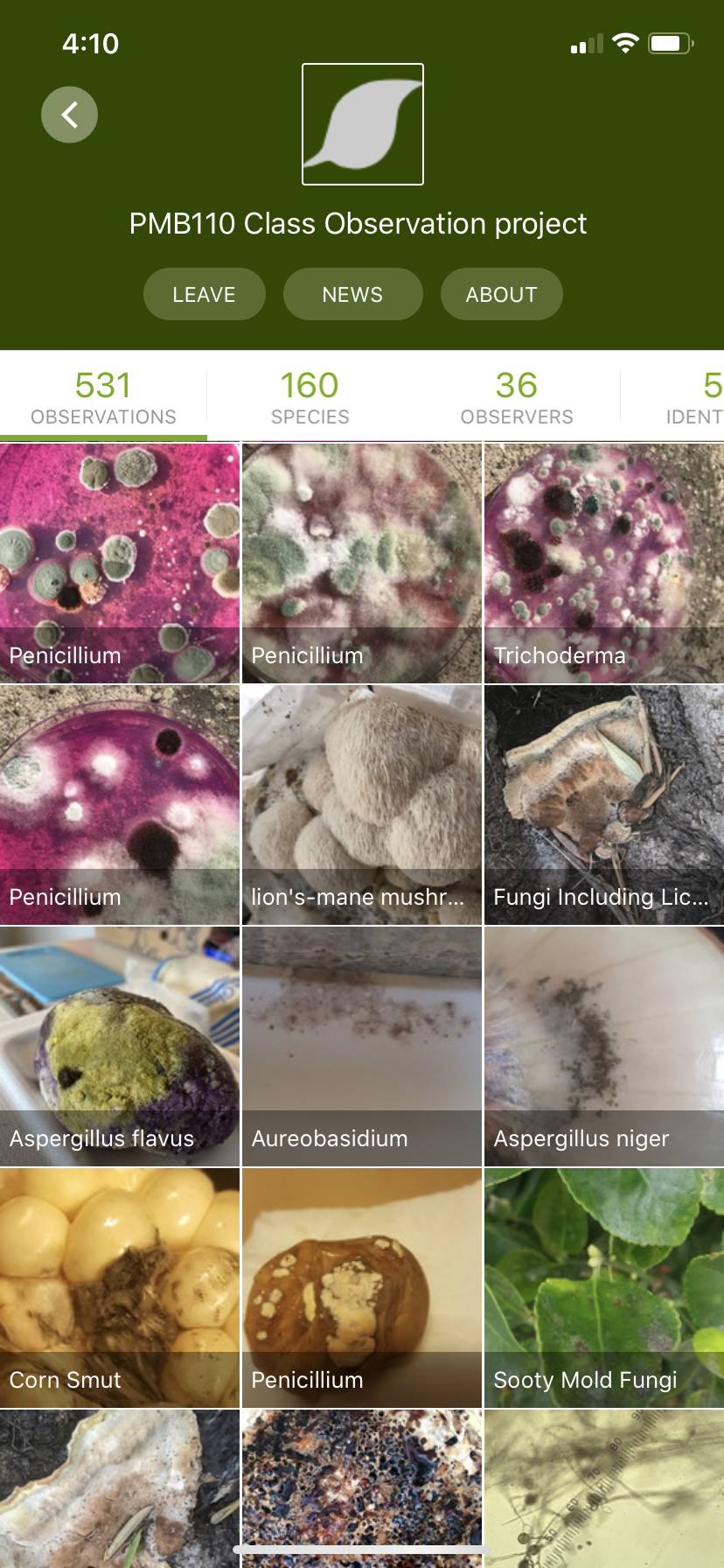

Using iNaturalist, an app and online global community for identifying plants and animals, students in professor Tom Bruns’ class shared images for specimen observation and identification. The students grew fungi at home with equipment mailed out by Bruns and participated in online class “fungi show and tell” discussions.

Other faculty have adopted creative workarounds by using the post office for remote learning. Tom Bruns, a professor of plant and microbial biology, mailed students in his Biology of Fungi course petri dishes with instructions and a base of nutrients for growing fungi.

Bruns designed the Fungal Diversity Observation Project to demonstrate the diversity of fungus that exist in almost every environment, while teaching his students about specimen observation and identification. After the students grew the samples of fungi that they collected, the class began each online lab with a "fungal show and tell,” discussing the images, observations, and methodology for studying specimens.

"I think the students enjoyed the Petri dish sampling, and it allowed them to see some of the common fungi in their home environments," says Bruns. "When we return to having a real lab, rather than a virtual one, it would be easy to expand this exercise by incorporating microscopic examination and nucleotide sequence analyses."

Using their smartphones, students posted images and observations on the iNaturalist website that depict a fungus or, if found outside on a plant, the associated symptoms that the fungus causes. The class could also leverage the iNaturalist online community of specialists and citizen scientists to learn about specimens, before coming together with the class to share results. Finally, students in the course completed a research component by classifying the fungus by its scientific genus and species.

From the lab to the kitchen

For Sarah Minkow, a dietitian and lecturer in the Department of Nutritional Sciences and Toxicology, the coronavirus pandemic also presented a significant challenge for her teaching. She teaches Personal Food Security and Wellness (NUSCTX 20), a course designed to provide cooking and nutrition skills to students experiencing food insecurity. In normal years, students attend lectures and labs in the Cal Teaching Kitchen, where they learn hands-on nutrition, recipes, and cooking techniques.

“There are various levels and kinds of food insecurity,” says Minkow. “It includes not having access to nutritious food, but also not having the skills or knowledge of how to cook for oneself. So the course focuses not only on bolstering skills and knowledge of cooking and nutrition, but also on providing information on crucial financial resources to students.”

Initially, when the pandemic was on the rise in April, Minkow and other lecturers who teach courses in the on-campus kitchen tried buying groceries in bulk and distributing them to students to cook at home. But with over 50 students, the distribution process ended up being difficult logistically and too wasteful. Instead, the class distributes gift cards for a supermarket so students can purchase ingredients themselves, adding the educational benefit of teaching students about shopping for groceries.

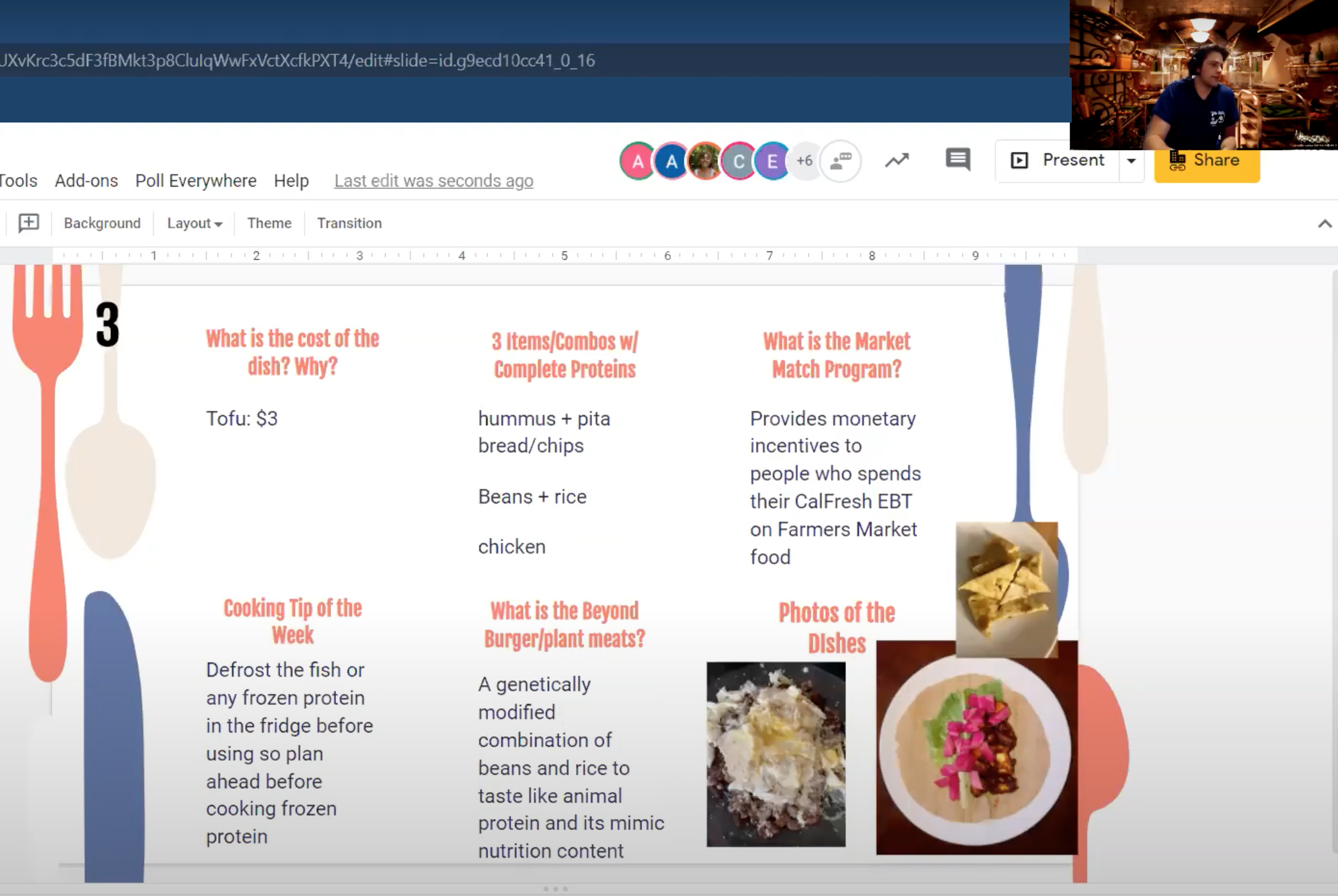

With her graduate student instructor Ryan Farquhar, a graduate student in the School of Public Health, Minkow restructured the course with online lectures followed by labs that include home cooking. First, Minkow gives the main lecture on nutrition—say, for instance, on calculating specific calorie and nutrient needs. For the lab component, Farquhar holds a mini-lecture that introduces students to a particular theme, such as grains or proteins, and goes over recipes with the class.

Ryan Farquhar discusses recipes and cooking methods with his students over Zoom.

Students then break into groups and film themselves cooking the selected recipes. Afterwards, the class comes together on Zoom to discuss the experience, ask questions, and share observations and feedback.

Early in the process, Farquhar noticed that students were logging in from wildly different time zones—some from areas as distant as Japan, Thailand, and South Korea. He quickly realized that some students were waking up at 5am to cook meals, so he changed the course to allow an asynchronous option.

While Farquhar says that he misses being able to assist students in person, he noticed that remote cooking was more efficient. In the campus kitchen, stoves and sinks are generally shared by two groups, but with each individual having access to their own workspace, they can go through recipes more quickly. The new lab format provides more time for mini-lectures, deep-dive discussions, and explanation of available resources offered through the Basic Needs Center and other programs.

"One of the great things about this course is being able to see students’ confidence in the kitchen grow over time," says Farquhar.

Though Minkow acknowledges that the course this semester misses out on the more communal elements—for instance, regular class meals that are an important component of social bonding and interaction—she notes that moving online could have the surprise benefit of expanding access. “Previously, enrollment in this course was much more limited by what the kitchen could accommodate,” says Minkow. “Now students can complete the cooking labs from the comfort of their own kitchens. Our hope is that, in the future, we can secure enough funding and increase the NUSCTX 20 class size so that any student, anywhere, who is struggling with food insecurity has access to learning how to adequately nourish themselves.”

Exploring outdoor instruction

Students Joseph Toman, Christina Shulte, Moe Sumino, and Gabriel Perez participated in the outdoor in person teaching pilot on November 17th. In this lath house, roots and tops of 100 grass plants were cleaned and separated for drying and weighing. Photo by Lynn Huntsinger.

Though remote learning has been successful, many at the College are eager to safely return to campus. To that end, Huntsinger is one of several faculty working with the university to determine if outdoor meetings could be held safely next semester.

Huntsinger leads a pilot program to evaluate protocol for outdoor education and survey students to gauge interest. Currently, at least four pilot courses are under review, and she says that the initial results are promising.

“I do think the students really want to be on site,” says Huntsinger. “They love the physical connection of being in the lab and interacting with the plants. So we’re hoping to set up a process next semester where, if someone is teaching a class, a teacher can propose an outdoor session,” says Huntsinger. “We're still developing the protocol but I’m optimistic. Our faculty is very innovative.”