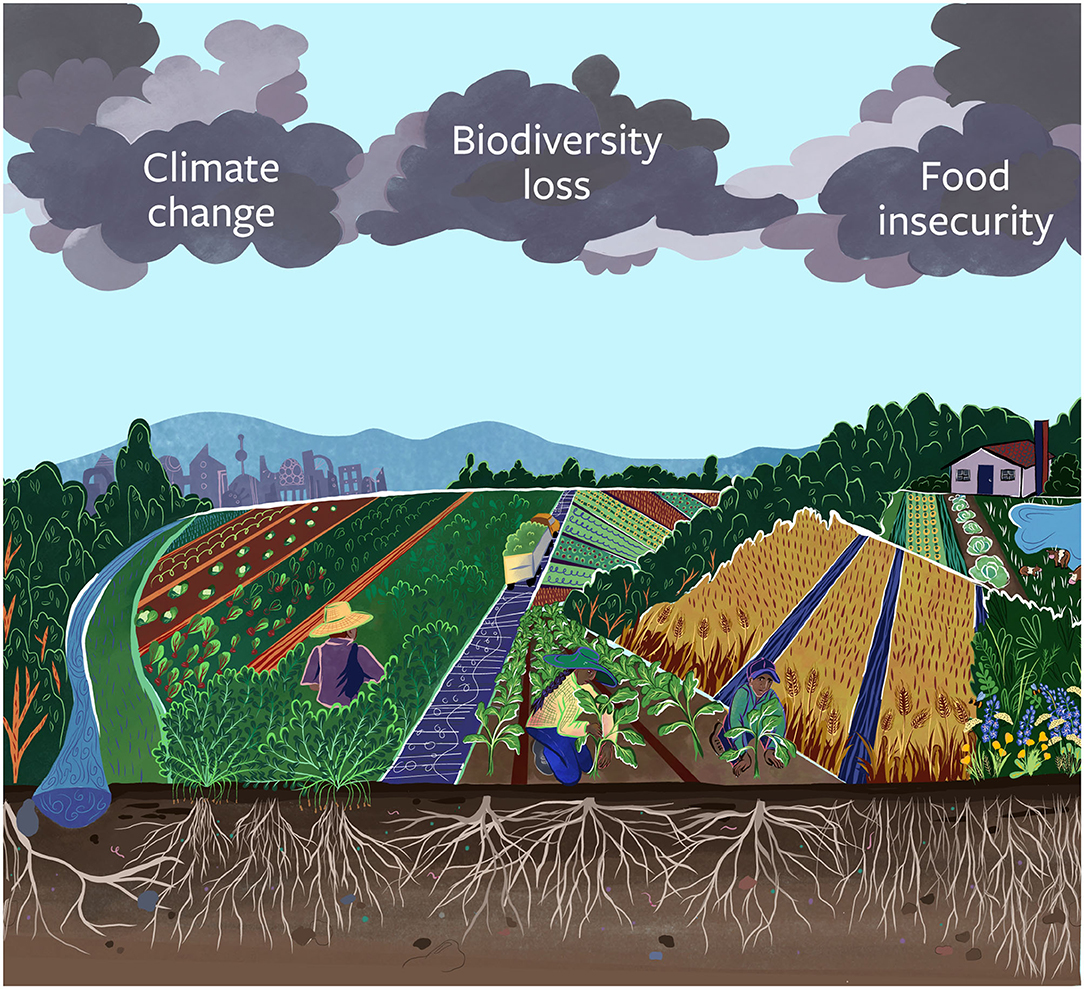

Agriculture and food production emit 23 percent of greenhouse gases worldwide, drive biodiversity and habitat loss, contribute to economic decline in rural communities, and displace traditional knowledge and practices around food. At the same time, the global “triple threats” of climate change, biodiversity loss, and global food insecurity are putting strain on numerous levels of food and agricultural systems, from producers and workers all the way to consumers.

A recent study co-authored by a group of researchers in the Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management (ESPM) raises critical questions about how agrifood systems can best adapt to future shocks and stressors, and investigates ways that these systems can undergo transformative, systemic change, in order to reduce environmental degradation and mitigate social inequities.

The Anthropocene “triple threat”—climate change, biodiversity loss, and global food insecurity—interact in ways that will exacerbate long-standing climatic, ecological, socioeconomic, and political challenges for agriculture and food systems. Graphic via Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems.

Simplification and diversification in agrifood

Published in the journal Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, the study analyzes two overarching trends in agrifood systems—simplification and diversification.

Over the past hundred years, agrifood systems have tended increasingly towards simplification, a more centralized, hierarchical model in which fewer producers can intensify yields and increase profit. Monoculture corn or soy in the United States, as well as massive livestock feedlots, exemplify such consolidated operations. Simplified systems often rely heavily on non-renewable synthetic inputs like agrichemicals and create negative externalities like pollution or soil erosion—problems for which society as a whole must pay.

“Simplification pathways seem to promise farmers greater uniformity and control, in which consolidated markets are dominated by these large-scale enterprises owning lots of land,” says Margiana Petersen-Rockney, a PhD candidate in ESPM and lead author of the study. “Simplification generally corresponds with ecological simplification,” she adds, “as producers move towards more homogenized systems specializing in just one or two crops or livestock varieties.”

Diversification, on the other hand, focuses on fostering social-ecological complexity as a means of improving outcomes for more people, benefiting natural systems, and integrating resilience to shocks and upheavals. Such processes can leverage natural technologies to enhance biodiversity, improve stability in and protect ecosystems, reduce the need for inputs like fertilizer and pesticides, and provide other positive outcomes for workers and consumers.

“We found that all three of the triple threats are mitigated in more diverse agricultural pathways, whereas they tend to be worsened in simplified systems,” says Petersen-Rockney. “Importantly, we know that a lot of the negative impacts are disproportionately felt by marginalized communities.”

The authors find that diversification can break agrifood out of damaging cycles while bolstering environmental sustainability and social equity. Diversification can create more broad and nimble adaptive capacity—defined as the ability to adapt to changing circumstances like droughts or market shocks—while simplification tends towards more narrow and brittle adaptive capacity.

“Simplification can do a fairly good job of dealing with narrowly defined problems in isolation,” says assistant professor Timothy Bowles, a co-author and lead faculty on the study. “But increasingly, problems related to climate change and food security are acting on agrifood systems simultaneously, and in such instances, diversified systems tend to be more resilient and have a higher capacity for dealing with disruption.” He offers the example of genetic engineering that can create strains of drought-resistant crops but may fail when another challenge—for instance, an insect pest or pathogen outbreak— compounds the problem.

The study, conducted over two years by researchers in the Berkeley Food Institute’s Center for Diversified Farming Systems, began with a comprehensive analysis of the literature on agrifood systems. The multidisciplinary team of researchers then broke into groups based on their research backgrounds and specializations. In particular, they focused on connecting the more substantial literature on ecological sustainability and agroecology to the less-studied social aspects—for example, institutions, market structure, and power hierarchies—of farming systems.

“In the literature around agriculture, you often see these terms like sustainable intensification, climate-smart agriculture, and others,” says Petersen-Rockney. “However, a lot of research is pretty agnostic about the actual processes used to meet these goals. With this study, our group focused on the widely variable ways such practices are actually implemented in the world.”

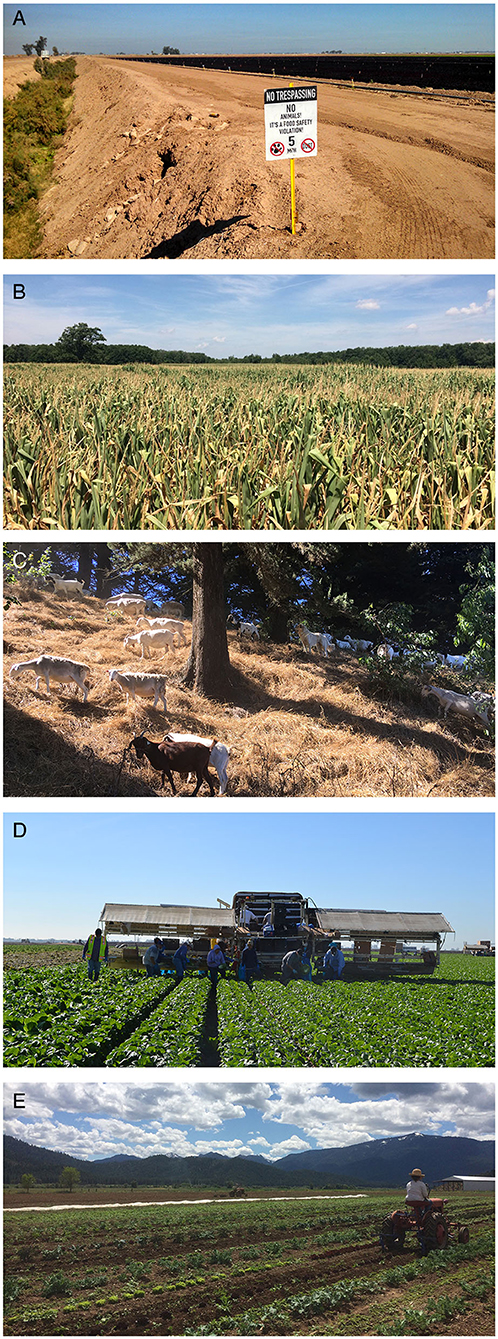

Five cases of challenges in which farming systems must adapt to the triple threat: (A) Photo by Patrick Baur; (B) Photo: Leah Renwick; (C) Photo: Margiana Petersen-Rockney; (D) Photo: Patrick Baur; (E) Photo: Margiana Petersen-Rockney.

Resilience in five case studies

To understand simplification and diversification in agrifood systems, the researchers focused on equity and sustainability outcomes across five cases, primarily in the United States: drought, foodborne pathogens, farm labor, marginal lands, and land access and tenure.

In the analysis on foodborne pathogens, they find that diversified systems are more resilient. Various zoonotic diseases can be found with animal production and concentrated feedlot operations, and in recent years, spinach and lettuce producers in California have been plagued by outbreaks of E. coli. While past simplified approaches have called for the removal of wildlife from farms, Bowles notes, research has now shown more biodiversity naturally helps to regulate pathogens like E. coli, even as it promotes other ecosystem services like soil and water retention.

Diversification can also help agrifood systems adapt to droughts, which are expected to become more intense and frequent due to climate change. Across agricultural landscapes, drought damages farmers' ability to raise livestock, grow crops, and sustain a viable livelihood. As just one example, the study states that moderate and severe droughts struck around two-thirds of the continental United States in 2012, leading corn production to fall about 25 percent and causing global price spikes across the market. Bowles says that crop diversification on a single farm can not only improve soil health and bolster corn’s resistance to drought, but it can offer alternate revenue opportunities for growers when commodity prices fluctuate.

Systems that embrace diversification practices can also create benefits for labor and expand access for small-scale farmers. Currently, agricultural workers in the United States are poorly paid, lack significant legal protections, and face challenging and dangerous working conditions. In addition, say the authors, the consolidation of farms has made entry into agriculture more difficult, further solidifying the socio-economic disparities between owners and workers.

Less affluent farmers often go into debt to lease land, at which point they are too locked into a market and production system to try alternate practices. Petersen-Rockney notes that, because many diversified practices and strategies are far less capital intensive, such models are more accessible to a wider range of farmers, including people with limited resources or on marginal lands.

“When considering diversification models as related to labor, it’s important to consider who is farming in simplified models,” says Bowles. In the United States, 98 percent of farmland is owned by white people, despite 78 percent of labor being done by people of color, he points out. “Diversification can help dismantle the structure that has created those inequities and make the system much more representative and equitable. Such practices can facilitate workers to have more discretion, autonomy, and better working conditions, as in many worker-owned farm cooperatives.”

The study authors affiliated with ESPM also include graduate students Aidee Guzman, Kenzo Esquivel, James LaChance, Mindy J. Price, Yvonne Socolar, and Paige Stanley, faculty members Kathryn De Master, Claire Kremen, and Alastair Iles, lecturer and alumnus Federico Castillo, alumni Patrick Baur and Adam Calo, former postdoctoral researchers Maria Mooshammer, Joanna Ory, and Franz Bender. The full study can be found on the Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems journal website.