A Black rhino after being relocated to a protected area. Photo by Charli Pretorius.

Active restoration of wildlife is critical in halting the global biodiversity crisis. Wildlife restoration efforts, which include the reintroduction of individual animals and the recovery of key habitats, have supported the return of wolves to the American West, Andean condors to Patagonia, and Chinese alligators to the Yangtze River. But for every successful attempt, many restoration efforts fail to overcome the very same human conflicts that led to their population decline.

A new study from a team of UC Berkeley researchers may offer conservationists clues on how to improve the outcomes of future wildlife restorations. The first-of-its-kind analysis, published today in Nature Communications, found that partnering with local communities and setting goals relating to the social, cultural, political, or economic aspects of wildlife restoration efforts made each attempt significantly more successful.

“Efforts to restore wild populations and ‘rewild’ ecosystems increasingly capture public attention but can be socially and politically divisive,” said lead author Mitchell Serota, a PhD candidate in the Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management (ESPM). “Our work shows that the long-term success of restoration attempts relies on public support and local buy-in.”

Examining successful and unsuccessful wildlife restoration projects can give us a better understanding of what factors contribute to success, Serota said, which is paramount to preventing future loss of biodiversity. To do so, the authors analyzed over 300 wildlife restoration attempts conducted in 80 countries from the 1960s to the present day. They found that proactively engaging local partners and including economic, educational, cultural, and other objectives during the planning process made positive outcomes 10 percent more likely.

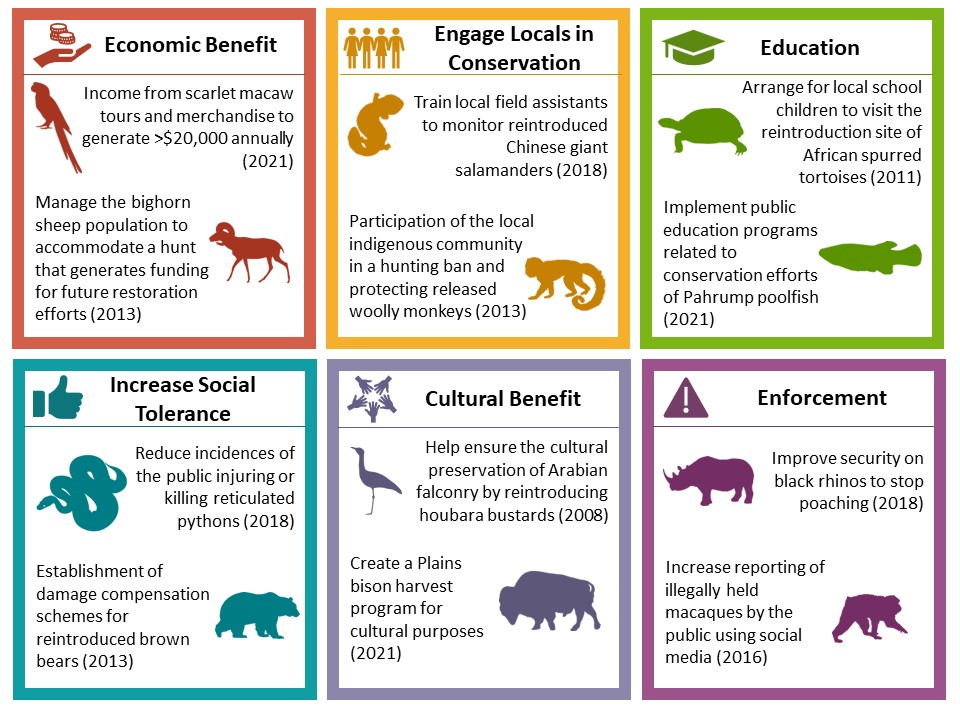

Strategies were identified based on human dimensions reported in project goals or success indicators from case studies in the IUCN Global Re-Introduction Perspective Series; the figure includes key examples from each strategy. Image by Serota et al.

“A lot of people in conservation organizations have gone the extra mile to engage communities in local wildlife restoration efforts for a long time,” said ESPM professor Arthur Middleton, the study’s senior author. “What’s exciting about this study is that it resoundingly validates their efforts through the first global, quantitative review. ”

In Kenya, the Sera Conservancy partnered with local community members and government representatives to successfully reintroduce the Black rhino after a 20-year absence. The Sera Conservancy taught local community members how to properly monitor the rhinos and worked to develop a participatory management plan that addressed potential conflicts like disease risk to cattle and environmental impact, and benefits like potential revenue streams.

The 13 rhinos reintroduced as part of the management plan began to breed after one year, and the population now has a growth rate of 20 percent. Serota said bottom-up approaches like community-based conservation, which centers the needs and wants of local communities, can improve the ability of humans and wildlife to coexist. "These approaches can increase trust and learning between conservationists and local communities, ultimately leading to better outcomes for everyone,” he adds.

Additional UC Berkeley co-authors include PhD students Kristin Barker, Samantha Maher, Avery Shawler, and Guadalupe Verta; alumni Wenjing Xu (PhD ’22 ESPM), Chelsea Andreozzi (PhD ’22 ESPM), Elizabeth Templin (MS ’21 Rangeland and Wildlife Management), and Gabe Zuckerman (BS ’19 Conservation and Resource Studies); and West Virginia Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit staff member Laura Gigliotti, a former postdoctoral researcher in the Middleton Lab