From left: George Meléndez Wright, Benjamin Thompson, and Joseph Dixon at Mono Lake. Photograph by Frances Chamberlain. Courtesy of Jerry Emory.

More than 90 years ago, a trio of UC Berkeley-trained researchers helped integrate the principles of science and ecology within the U.S. National Park Service (NPS), ushering in a new era of land and wildlife management for the nascent government agency.

To honor that legacy, Rooms 304 and 205 in Hilgard Hall—where George Meléndez Wright (BS 1927 Forestry) and his colleagues Joseph S. Dixon and Ben H. Thompson worked—are now affixed with door plates and accompanying Braille plaques bearing their names. The door plates, which recognize their work on establishing the first wildlife division within the NPS, were unveiled May 5 before a small crowd of National Park Service staff, UC Berkeley faculty and staff, and friends and relatives of the Wright family.

“We can all attest to the importance of science in key decisions on natural and cultural resources within our National Parks, but that wasn’t always the case,” said Patrick Gonzalez (PhD ’97 Energy and Resources), an associate adjunct professor in the Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management. “That started to change 90 years ago in this office with George Meléndez Wright.”

Historians often credit Wright and his colleagues with making the case for science-based natural resource management of the national parks. Conservation writer Jerry Emory said the first two directors of the NPS, Stephen Mather (UC Class of 1887) and Horace M. Albright (BS 1912 Economics), were primarily concerned with creating basic infrastructure in the parks and providing entertainment for tourists.

“Mather first had trains coming to the parks, and eventually they started building roads to get cars into the parks. Wright was concerned about the ecosystem, the wildlife, and how to manage the larger landscape,” Emory (MA ’85 Geography) said.

A pioneering naturalist, Wright studied forestry and zoology under UC Berkeley professors Walter Mulford and Joseph Grinnell. He joined the NPS as an assistant park naturalist in Yosemite after graduating from UC Berkeley in 1927, becoming the first Spanish-speaking professional in the NPS. He soon grew concerned about the lack of scientific research and data about the parks, as well as practices across the NPS system: rangers fed wildlife for spectators, or killed natural predators like wolves, cougars, and coyotes, selling their pelts to supplement their wages.

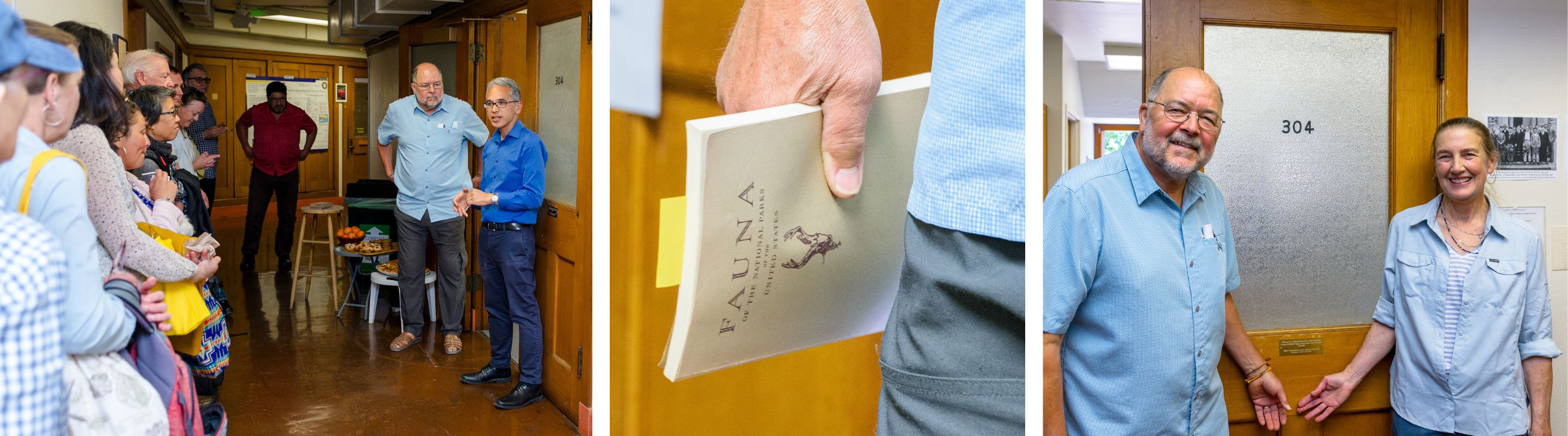

From left: Gonzalez speaks to a crowd of NPS staff, UC Berkeley faculty and staff, and friends and relatives of the Wright family. Emory holds a copy of Fauna of the National Parks of the United States. Emory and his wife, Jeannie Lloyd, one of Wright’s granddaughters, pose with the plate installed on the door leading to Room 304. Photos by Mathew Burciaga.

With Albright’s approval, Wright established a wildlife survey office for the NPS in 1929 and privately financed a three-year survey of wildlife and plant conditions in the national parks. He recruited Dixon, a staff member at the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology and former student of Grinnell’s, and Thompson (MA ’32 Vertebrate Zoology), who had just been admitted to UC Berkeley for graduate study. Emory said that, as part of their deal with Albright, the trio wanted to publish their findings so others across the parks system could learn from their research.

“They would spend the season, from early spring through late fall, doing all their field work, and during the winters, they were in this building writing,” Emory said.

In 1931, the group had moved into Hilgard Hall from their downtown Berkeley offices, and by 1933, the survey group was reorganized into the NPS’ first Wildlife Division. Dixon and Thompson were brought on as staff biologists, and Wright was appointed Division head—a position he held until his untimely death in a vehicle accident in 1936. Their research, along with 20 policy recommendations to improve parks and wildlife management, was published in 1933 and 1935 as the first two entries in the Fauna of the National Parks of the United States series.

Wright (front row, third from right) and classmates in front of Hilgard Hall.

Gonzalez—who worked for the NPS as the lead for climate change science from 2010 to 2021—said he first began looking into Wright’s history in Hilgard Hall after the agency moved his duty station from Washington, D.C., to Berkeley in 2015.

“A colleague in the Washington office asked me, ‘You work at Berkeley—where is George Wright’s office?’,” he recalled. “George Meléndez Wright is extremely well respected among National Park Service staff, so the question has always been at the back of my mind.”

Gonzalez connected with Emory, whose latest book, George Meléndez Wright: The Fight for Wildlife and Wilderness in the National Parks, celebrates Wright’s vision and offers a historical account of a crucial period in the evolution of U.S. national parks. Emory examined Wright’s historical correspondence and found Hilgard mailing addresses with Rooms 328 and 213. Tony Gamez, facilities director for Rausser College of Natural Resources, then told Gonzalez that the university had since changed the room numbers in Hilgard Hall.

“Tony really likes history,” Gonzalez said. “He had these nice original plans of the building, which showed the room numbers.”

Room 328 has since been renumbered 304; it is currently utilized as lab space by Associate Professor Ian Wang. Room 213 is now 205 and is used by the lab of Professor Dennis Baldocchi.