Photo courtesy of Nikita Bahadur

Nikita Bahadur chose UC Berkeley for the unique molecular environmental biology program offered by Rausser College of Natural Resources.

As an undergraduate, Bahadur immersed herself in research opportunities offered across campus. In addition to working in several labs on campus, she completed a College honors thesis under the supervision of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management and Integrative Biology professor Todd Dawson, and spent a semester studying at UC Berkeley’s Gump Station on Mo’orea, French Polynesia.

“It’s a pretty unique and special experience,” said Bahadur. “You don’t know what to expect when you sign up to study on an island for a couple of months, but I met some really close friends there and had an amazing time.”

On Sunday, Bahadur will cap off her UC Berkeley experience and join the ranks of the more than half a million living UC Berkeley alumni as a member of the Class of 2025. She spoke to Rausser College about her UC Berkeley experience before commencement.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Why did you choose UC Berkeley?

UC Berkeley stood out because of Rausser College of Natural Resources, which was unique to the University, and the molecular environmental biology (MEB) major sounded like exactly what I wanted to study. When I was in high school, I did summer internships with the Climate Corps run through Climate Action Santa Monica. It was a lot of lobbying, political activism, and marches, which I liked because I was interested in environmental conservation issues.

Bahadur at the UC Berkeley Botanical Garden.

But I was mostly interested in the scientific and biological aspects of environmental studies, and wanted to learn more about molecular approaches to solving environmental problems, so MEB was a great fit for me. It felt kind of perfect—I didn’t find anything like it anywhere else.

What classes did you enjoy most?

I liked plants coming into college, but I really got into them after taking The (Secret) Life of Plants (PLANTBI 40) with professors Ben Williams and Patrick Shih. It was exciting to explore plants in a way that felt like learning an odd and special collection of fun plant facts. We learned about plants like the bladderwort, which has a pressure system capable of sucking in insects and other prey, and plants that use exploding pods to spread their seeds. People sometimes think of plants as passive organisms, but when you look deeper, they’re actively doing intricate things all the time.

I also loved Plant Physiological Ecology (IB 151), which I took with Professor Todd Dawson last spring. That class kick-started my interest in the field and led me to my senior honors thesis. We took a class field trip to Blue Oak Ranch Reserve, where we took water potential data and plant physiological measurements in the field. It was a super amazing and educational experience, and I knew it was something I wanted to do more. When that class was over, Professor Dawson agreed to mentor and advise me on my honors thesis

What was your honors thesis about?

I was initially interested in the microbial community that lives on a leaf, but for my honors thesis, I decided to study the cuticle—the waxy outer layer of a leaf’s surface. Specifically, I wanted to examine how leaf cuticle manipulations affect wettability and foliar water uptake in five species of California native plants.

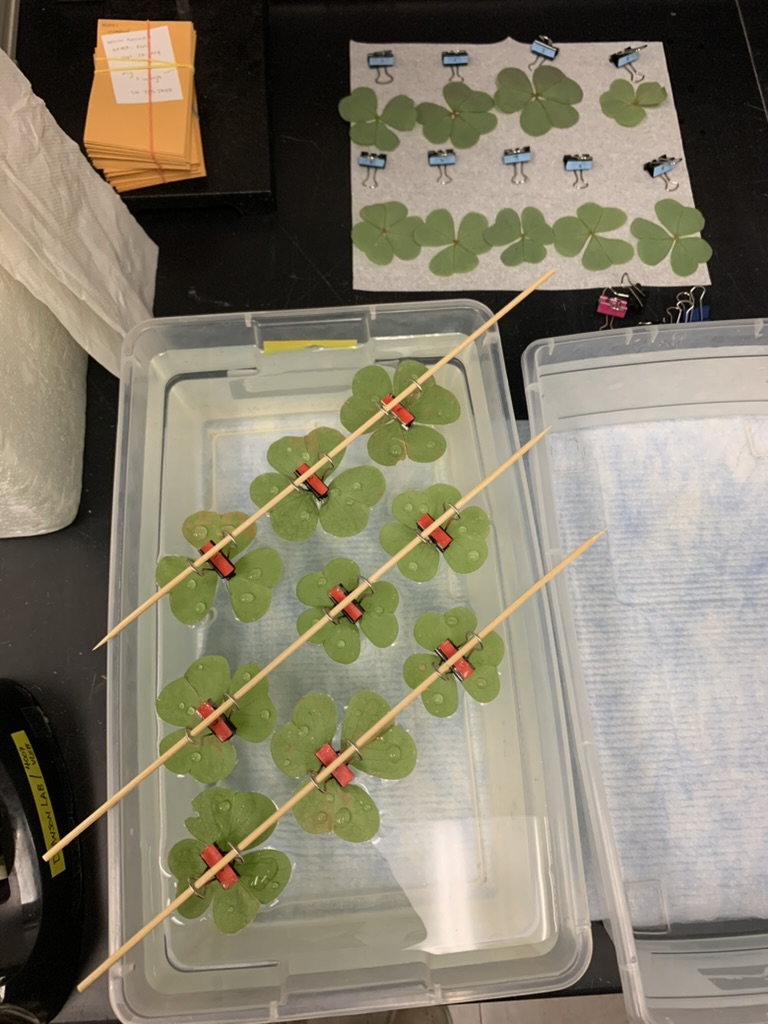

One of Bahadur's experiments in the Dawson lab.

For my research, I collected samples at the UC Berkeley Botanical Garden and worked in the lab to see how taking the cuticle off the leaf surface affects how much water it takes in and retains. This was a very rewarding project, but at times it was difficult, especially during the Fall semester when I did all my data collection. On Thursday nights, I would have to stay in the lab late—sometimes past midnight—to finish all foliar water uptake tests. Those tests required me to take a leaf, seal off the petiole (the stalk that joins the leaf to a stem), and submerge it in water for three hours in the dark. Once that was finished, I would weigh the leaf in 10-minute intervals over the course of an hour to determine the change in mass, which corresponds to how much water the leaf absorbs and retains.

While plants usually take in water through their roots, some absorb water through their leaves too, known as foliar water uptake. In the future, if the climate gets hotter and drier, then plants might begin to develop a thicker cuticle because they're scared of losing all their water. But if a plant that is used to pulling in water through its leaves develops a thicker cuticle, it may affect the amount of water it lets in and could add to its drought stress. Even though I couldn’t manipulate what would happen if the plants were in drought for 20 years, my experiment showed me that the cuticle is very important for foliar water uptake in some—but not all—plants, which was fascinating.

Are there any faculty or staff who supported you during your time at Cal?

Working with Professor Dawson was great. He knows a lot about the field of plant physiological ecology and is very knowledgeable about the literature. Anytime I had a question, he could point me to a paper that I could read to learn more. I also learned a lot from the Botanical Garden staff members who helped me collect my samples, and the folks in the Electron Microscope Laboratory who helped me with microscopy imaging.

Professor Rachel Brem has also been really important for my professional journey, in particular. I took her Biology of Fungi class last semester and learned so much from it. She’s helped me out a lot this past semester while I was looking for jobs after graduation, and has encouraged me to continue exploring fungal research.

What was your time on Mo’orea like?

I learned about the Mo’orea program around the end of my freshman year. I love tropical ecosystems, so I thought it would be a great fit for me, and I’m so glad I was able to do it!

Left: Bahadur harvesting coconuts on Mo'orea. Right: Samples from her research project on coconut germination.

The whole biome of Mo’orea is incredibly diverse in that there are both terrestrial and marine ecosystems to explore. We spent the first couple of weeks learning more about the island’s ecology through lectures and field trips guided by the professors. After that, we were given a lot of freedom and independence to explore topics for a potential research project. We had time to collect pilot data and draft proposals outlining our projects. The majority of the class was spent working independently on our individual research: we would schedule times to go into the field with a buddy to collect our data, run experiments in the lab, and then write the paper. We had progress check-ins every two weeks, and we had to keep ourselves on track to meet these deadlines.

My project focused on the germination of coconuts. They’re all over the island and are an important plant for Mo’orea’s Indigenous communities. They’re also a big indicator of the ecological health of the island. To me, the germination process of coconuts is kind of wacky. Coconuts have a liquid and solid endosperm inside, known as the coconut meat and water, but when they germinate, the harder endosperm begins to break down and fills the cavity with a fluffy structure called a haustorium. I had never seen that before and wanted to know more.

My project investigated the environmental conditions that induce the formation of the haustorium and the chemical properties of that tissue. I found that, if you soak coconuts in fresh water for a few days and then stick them in the ground, they're more likely to germinate than if you don’t soak them. The coconut’s distance from the shore also ended up being a significant predictor of germination. I also found that the haustorium itself was slightly cytotoxic, which was interesting—I thought it must provide the coconut with some kind of protection from herbivory, in addition to making sure it has enough moisture and nutrients to grow.

Bahadur during a Cal Band performance on Sproul Plaza.

How did you spend your time outside of class?

My older brother joined Cal Band when he was a student here, and I thought it was cool to watch their shows when I would come visit. I wound up joining Cal Band in my first year as well. I played flute from elementary through high school, but played piccolo my first year in band (it’s the closest analog in Cal Band). I decided to switch instruments in my second year, so I learned the trumpet.

Cal Band is a big commitment; I’m at every home football game through the fall, in addition to some meets for other sports like basketball, gymnastics, and volleyball. There are two-hour rehearsals each day through fall, and Saturday game days are an all-day event. It’s exhausting, but for me, it was a great way to build community at Cal.

What plans do you have after graduating?

Over the summer, I'm participating in a summer research course offered by UC Davis’ Global Learning Hub. I’ll be in Thailand for about a month and a half studying microbiology. We’ll be exploring topics like foodborne illness, fermentation, and how humans impact the microbiology of food.

After that, I’ll be starting a new job in the lab of Plant and Microbial Biology professor Lotus Lofgren. I’m hoping to gain more research experience, learn about mycorrhizal fungi, and maybe co-author a publication. My eventual goal is to get a PhD, but I think I need to get a little more grounded in what I want to study. There are so many areas to explore, especially within plants and fungi, and I’m excited to apply all I learned from the MEB major in my future endeavors.

Do you know of a student or group in Rausser College involved in noteworthy research, community outreach, or extracurricular activities? Let us know by submitting a suggestion with this nomination form.