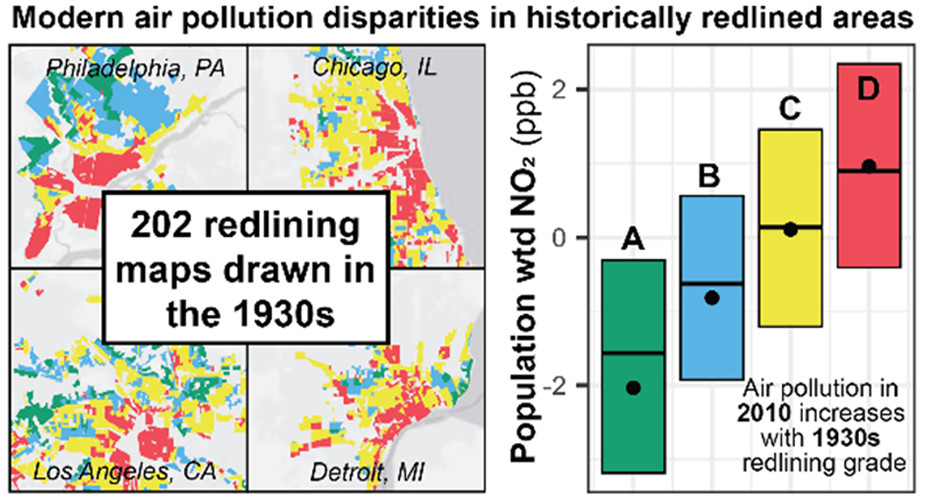

Neighborhoods that were subject to redlining, the discriminatory mortgage appraisal practice used by the federal government after the Great Depression, were found to have higher-than-average levels of air pollution, according to a major new study from a team of researchers at UC Berkeley and the University of Washington.

Published last week in the journal Environmental Science and Technology Letters, researchers examined 2010 air pollution data from 202 cities across the United States and found that people of color—largely Black and Latino Americans—live in areas with more smog and fine particulate matter from cars, trucks, buses, coal plants, and other nearby industrial areas than White Americans. Even within redlined neighborhoods, the authors found additional disparities between air pollution experienced by White and non-White residents.

"We know that these air pollutants ... have adverse health consequences and that these legacies of structural racism will have consequences—and are having consequences for community health," Environmental Science, Policy, and Management Professor Rachel Morello-Frosch, who co-authored the study, told National Public Radio.

According to Morello-Frosch, these findings highlight the lasting impact of structural racism in the U.S. Due to the disparate impact on people of color, the authors recommend policymakers prioritize targeted approaches to regulate emissions.

The study was co-authored by Haley Lane, a graduate student in the department of civil & environmental engineering; Joshua Apte, assistant professor of energy, civil infrastructure, and climate; and Julian Marshall of the University of Washington.

Read more »

NPR: Even many decades later, redlined areas see higher levels of air pollution

New York Times: How Air Pollution Across America Reflects Racist Policy From the 1930s